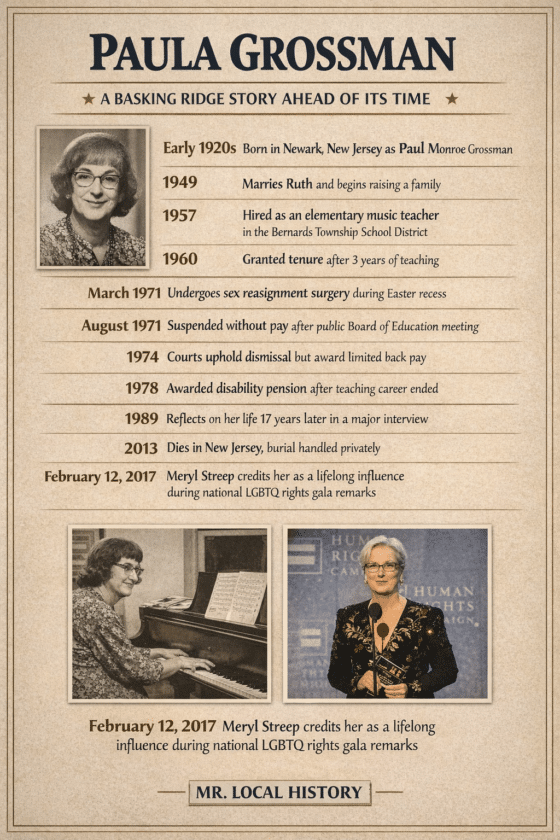

Paula Grossman’s dismissal from the Bernards Township school system in the early 1970s is widely regarded as one of the first public cases of transgender discrimination in American public employment. A tenured music teacher removed not for misconduct but for identity, her case was debated openly, litigated through state courts, and reported nationally at a time when no legal protections existed. Its lasting importance lies in how clearly it shows the gap between institutional authority and individual rights before the law caught up with lived reality.

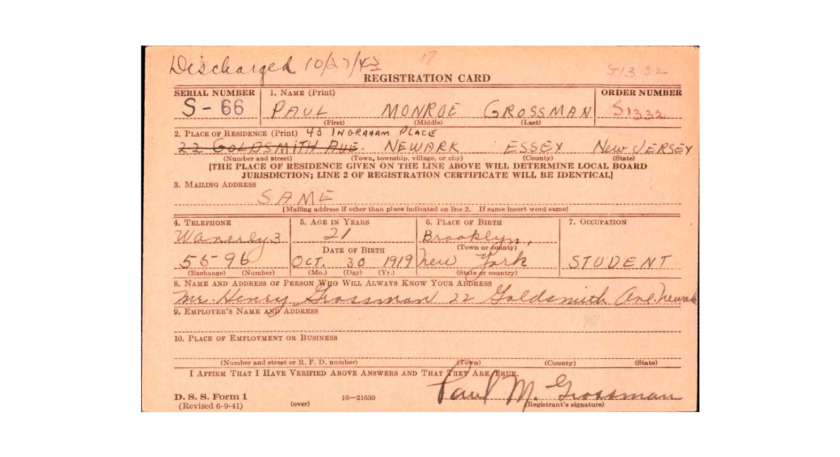

Paul Monroe Grossman was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1919 and grew up in a working and middle class urban environment in Newark, New Jersey during a period when social expectations around gender, family, and conformity were rigid. Contemporary reporting places his childhood in Newark, including early memories of family homes there, though the names and occupations of his parents are not consistently recorded in public sources. He was educated in New Jersey schools and went on to pursue higher education with a focus on music and education, earning the credentials required to teach in public schools.

After WWII, in 1949, Paul Grossman would marry Ruth Keshen in Maplewood, and together, they built a family life that would span decades and endure extraordinary circumstances. They raised their 3 children while Grossman pursued his teaching career, eventually settling in Plainfield, New Jersey, where the family maintained a stable home even as events later unfolded publicly. Their marriage remained intact after Grossman’s transition, a fact noted repeatedly in later reporting as rare and deeply significant.

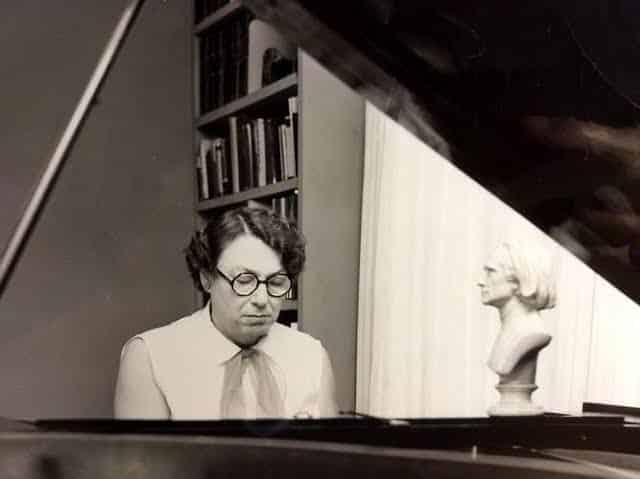

Grossman was hired by the Bernards Township School District in 1957, beginning what became a long and respected career as a music educator. He taught elementary and middle school students, including at Cedar Hill School and later Oak Street Junior High School in Basking Ridge. After earning tenure 3 years into his service, he spent more than a decade teaching music, accompanying students on piano, organizing lessons, and participating in school life without controversy. Former students and colleagues remembered a committed teacher whose professional identity was rooted in the classroom rather than in public attention.

Outside of work, Grossman lived what appeared to be a conventional postwar family life, balancing the demands of teaching with raising children and maintaining a household. Nothing in the public record from his teaching years suggests dissatisfaction with his performance or concerns about his conduct. This period of stability is essential context for understanding what followed. When events later thrust him into the public eye, the loss was not theoretical, but the loss of a profession, a routine, and an identity he had built over more than a decade.

Paul’s Shifting Identity and His 1971 Decision

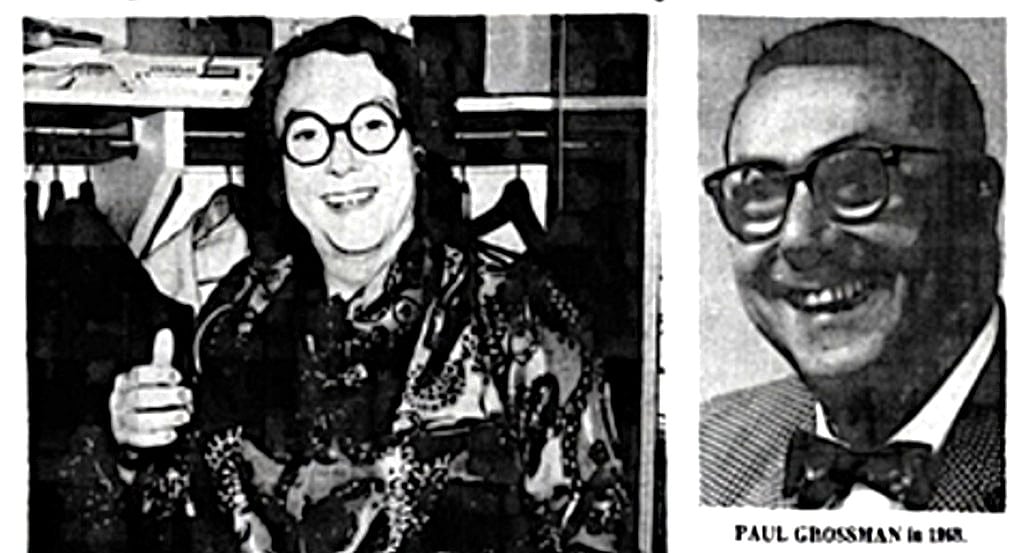

By the late 1960s, Paul Monroe Grossman had been teaching music in the Bernards Township School District for more than a decade and was a tenured, experienced educator. Privately, however, Grossman had been struggling for many years with gender identity, a condition later described in court records as worsening over time. In March 1971, during the district’s Easter recess, Grossman underwent sex reassignment surgery following medical diagnosis and treatment, a decision made after decades of internal conflict.

Grossman returned to complete the spring semester presenting as male, but during the summer of 1971 formally notified the school administration and the Bernards Township Board of Education of the intention to return in the fall as a woman, using the name Paula Grossman. This disclosure placed the Board of Education in an unprecedented position. With no clear legal guidance or policy addressing gender identity, the board consulted psychiatrists, reviewed educational standards, and considered community reaction. Board members expressed concern about potential disruption, public attention, and what they termed the possible psychological impact on students.

On August 19, 1971, after internal deliberations and a highly attended public meeting, the Board of Education voted unanimously to suspend Grossman without pay and later filed formal charges. The board did not allege professional incompetence, but argued that her continued presence could create notoriety and potential harm, citing “incapacity” under existing tenure law. This decision marked the beginning of a legal battle that would last more than 7 years and permanently end Grossman’s teaching career.

Post Transition

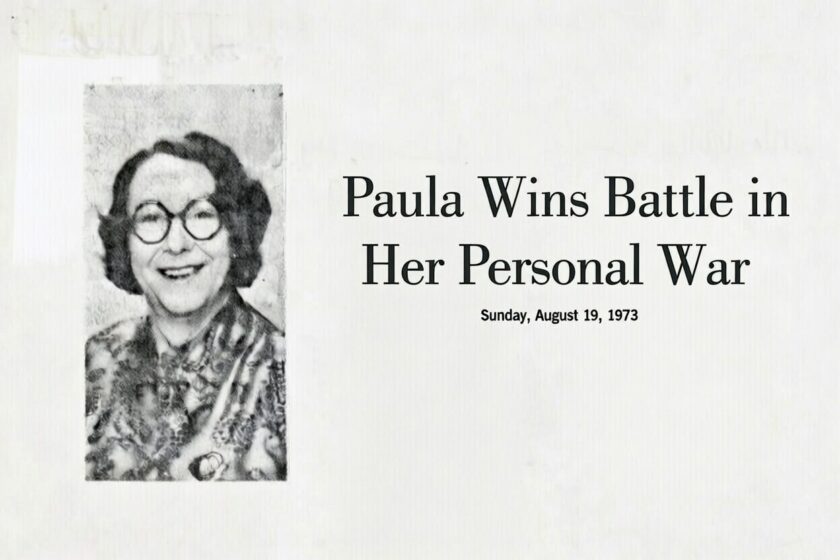

After her transition in 1971, Paula Grossman never returned to teaching. The Bernards Township Board of Education suspended her without pay in August 1971 and later dismissed her, and no court ruling reinstated her despite years of appeals. Courts acknowledged she was professionally capable, but upheld her dismissal based on claims of potential psychological impact on students, reflecting the legal standards of the era rather than her performance.

Shut out of public education, Grossman applied to more than 40 school districts without success. She supported herself by playing piano and lecturing before finding stable work with the City of Plainfield as an assistant criminal justice planner. In 1978 she retired with a disability pension after courts concluded her teaching career had been effectively ended.

Emotionally, Grossman described the years following her dismissal as difficult but not defined by regret. While anger over the loss of her profession lingered, she consistently stated that transitioning relieved the profound internal distress she had lived with for decades. Her family life remained intact. Grossman stayed married to the same spouse, Ruth, whom she had married in 1949, before, during, and after her transition. The couple lived together in Plainfield and raised their three daughters, who accepted her decision and went on to build their own lives.

In later years, Grossman turned to writing, authoring a handbook for transsexual individuals and working on her autobiography. Though she never returned to the classroom, her case became an early example of how the law once failed to protect people like her, a legacy recognized only years later as society and legal standards changed.

Note:

Penn State University states that data sources include Paula Grossman’s unpublished autobiography dated 1972. That strongly suggests it was a manuscript rather than a commercially published book. The Plainfield Public Library local authors collection state they hold a copy of “A Handbook for Transsexuals 1979” under author Grossman.

The Legal Battles and Public Perception

The legal record of Paula Grossman’s case is clear and clinical. Courts ruled that she was not professionally incompetent, yet upheld her dismissal based on speculative concerns about “potential psychological harm” to students. In the language of the law, Grossman lost because protections for gender identity did not yet exist. The rulings focused on disruption and perception, not on her abilities as a teacher.

Public perception, however, told a different story. Many former students remembered Grossman not as a legal controversy, but as a gifted and caring music teacher. Decades later, that memory resurfaced powerfully when Meryl Streep publicly credited Grossman, her sixth grade music teacher in Basking Ridge, as a formative influence. Speaking at a national awards event, Streep recalled Grossman’s courage, her dismissal, and the lesson it left on a young student about fairness, difference, and conscience. Streep emphasized that Grossman was a “terrific teacher” who never taught again, not because she failed her students, but because the system failed her.

This contrast defines Grossman’s historical significance. In court, she was reduced to a legal problem to be managed. In memory, she endured as an educator who mattered. The gap between those two views captures a moment when public institutions lagged behind human experience, and when the law could not yet recognize what students already knew.

Later Coverage: What the Record Shows

Later reporting on Paula Grossman focused less on courtroom drama and more on the long arc of consequences. After losing her bid for reinstatement, Grossman continued to pursue every remaining legal avenue available to her in the 1970s, including appeals through New Jersey courts and a petition to the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to hear the case. These efforts marked the end of her formal legal challenges. While she never regained her teaching position, courts ultimately ruled that she was entitled to a disability pension because her career had been effectively ended, even though she was not incompetent or physically unable to teach. That pension, awarded in the late 1970s, provided long-term financial stability. Earlier rulings also granted limited back pay totaling just over $4,000, but there was no large settlement, reinstatement, or damages beyond the pension.

Professionally, Grossman pieced together work during the years she was shut out of education. Multiple articles note that she played piano in New Jersey bars and nightclubs, both to earn income and to remain connected to music. She also lectured publicly through a speakers bureau and wrote extensively. Eventually, she secured steady employment with the City of Plainfield as an assistant criminal justice planner, a position she held for several years before retiring in 1978. This municipal job, combined with her pension, marked the first period of sustained financial security after years of uncertainty.

Later articles place significant emphasis on her family life, which remained remarkably stable. Grossman stayed married to the same spouse, Ruth, throughout her life, an outcome repeatedly described as rare in coverage from the 1980s and beyond. The couple continued living in Plainfield, New Jersey, and raised their three daughters together. The children accepted her transition, grew into adulthood, married, and moved on to independent lives. By the late 1980s, reporting describes the household as quiet, settled, and far removed from the public attention of earlier years.

Mentally and emotionally, Grossman’s later years were characterized by complexity rather than despair. She spoke candidly about anger that lingered over the loss of her teaching career and about the personal cost of standing her ground. At the same time, she consistently stated that transitioning resolved the profound internal distress she had experienced for most of her life. Later interviews emphasize that while she did not feel vindicated by the courts, she did feel whole as a person. Writing became a central outlet: she authored and revised a handbook for transsexual individuals and continued work on her autobiography, determined to control her own narrative.

Taken together, the later articles portray not a figure frozen in controversy, but a life that gradually stabilized. Grossman did not win her case in the courts, but she achieved financial security, family continuity, and a measure of peace. By the time later reflections appeared, including public recognition from former students decades later, the story had shifted from scandal to legacy: an early case that exposed how the law once failed, and how ordinary lives absorbed the cost of being ahead of their time.

Lessons Paula Grossman Took From Her Experience

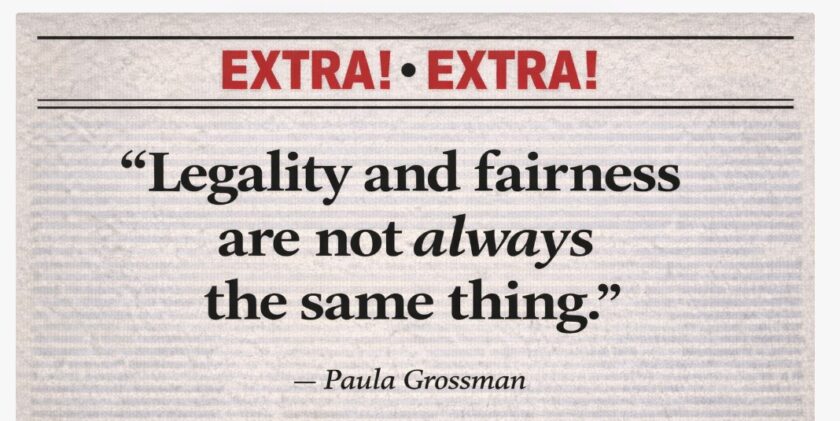

Paula Grossman often said that her greatest lesson was the difference between legality and fairness. She learned that the law can acknowledge a wrong and still allow it to continue when protections do not yet exist. She also came to believe that honesty has a cost, but hiding has a greater one, and she never regretted choosing to live openly, even when it ended her career. Another lesson she expressed repeatedly was that institutions move slowly, but individual lives do not pause while society catches up. Finally, she learned that identity and dignity are internal victories. While the courts denied her reinstatement, she believed that living truthfully gave her a sense of wholeness she had never known before.

Paula’s Passing

Paul Grossman passed on 26 September 2, 2003 at the age of 83. His wife, Ruth, would pass just two years later in 2005 at age 78. Paula was laid to rest privately, consistent with the quiet life she chose in her later years, long after the headlines faded but before the law fully reflected the arguments she had made decades earlier. She did not live to see the complete legal reversal of the standards that ended her teaching career, yet history ultimately moved in her direction. What began as a local school district decision in Basking Ridge became an early marker of how institutions respond when social change arrives before the law is ready. Grossman did not win her case, but she changed the conversation, and the quiet fact that her story would be handled very differently today is the clearest measure of her legacy. Her life reminds us that history is often shaped not by those who prevail in their own time, but by those who endure long enough for the world to catch up.

What Would Have Happened If This Occurred Today

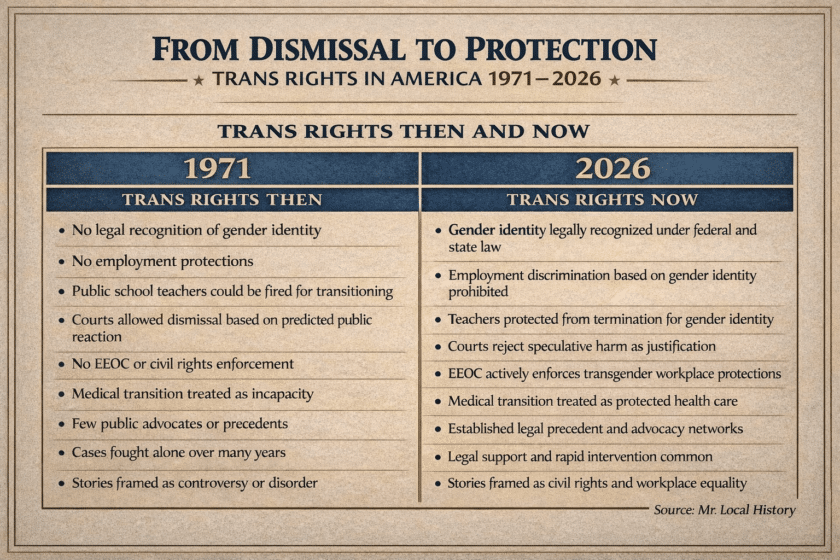

If Paula Grossman’s case unfolded today, the outcome would almost certainly be different. Federal law and New Jersey law now recognize discrimination based on gender identity as unlawful sex discrimination. A tenured teacher dismissed solely for transitioning would likely trigger immediate intervention by civil rights agencies, legal counsel, and union representation. Rather than years of appeals, the case would likely be resolved through reinstatement, accommodation, or a negotiated settlement.

Just as importantly, the story would probably never become a national controversy. School districts today operate under clear guidance and established policies, removing the uncertainty that defined the Bernards Township Board of Education response in 1971. The focus would be on compliance, not speculation about harm. In that sense, the most striking difference is this. If it happened today, Paula Grossman might never have become a symbol at all. Her story would be routine, quiet, and resolved early, and that quiet outcome would itself be the clearest measure of how much the world changed because people like her lived the story first.

Have a Comment or Story to Share?

We’ve been following this story for at least a decade, as Paula’s name has appeared a few times in social media circles. Many of those who attended elementary or secondary school at Cedar Hill or Oak Street, respectively, have all stated beautiful things about Mr. Grossman’s excellence as a music teacher. We hope those who have posted there find this story and post their comments and memories of a person who truly had a historic lifetime and forever has been captured in Basking Ridge’s history.

Post in the comments section below.