The year is 1926. Welcome to the “Board Bowl,” which had 80,000 fans and was one of the world’s greatest motorsport spectacles—and it was right here in New Jersey!

It’s funny how history weaves in and out of many of our stories and other research that becomes a new story. This story came about as we researched the history of beach racing in the Cape May area. Yep, the racing world was also firing up beach racing on the beaches in Daytona, which later turned out to be the beginning of NASCAR. Then we saw this photograph and said, “We gotta dig into this story!”

Jersey Motorsports Retrospectives: The Mr. Local History Project has a few researchers who love American motorsports. We’ve posted many stories about motorsports history in the Garden State. We welcome your comments and the end of this post.

Atlantic City Motordrome Visionary –

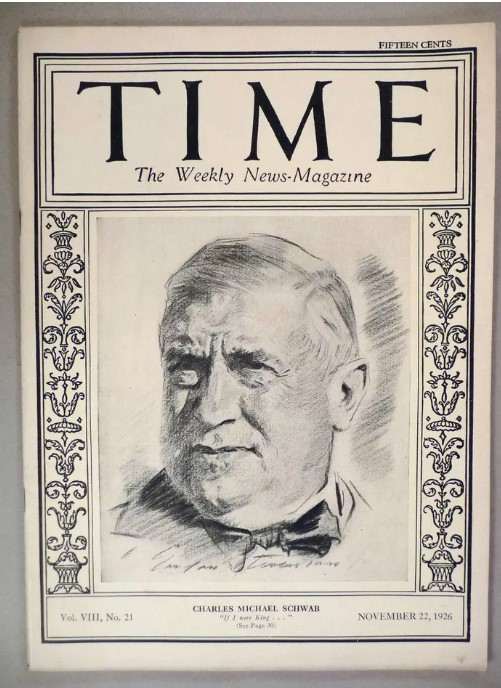

Charles M. Schwab – No Relation to the Stockbroker!

Charles M. Schwab (unrelated to the stockbroker) was the head of Bethlehem Steel. He was often nicknamed the “Master Hustler” for his high-energy approach and aggressive business tactics that transformed Bethlehem Steel into a powerhouse in the steel industry. His willingness to take risks, push boundaries, and innovate earned him this nickname among peers and the media. He was also sometimes referred to as the “Steel King” due to his significant role in the growth and dominance of American steel, rivaling even Andrew Carnegie.

Schwab was a major backer of the Atlantic City (Amatol) Speedway project, which aimed to repurpose the Amatol site into a premier motorsports venue. Along with support from the Atlantic City Speedway Association, this association included several investors and businessmen from the Atlantic City area who saw an opportunity to capitalize on the increasing popularity of automobile racing in the 1920s. It was noted that 20% of the U.S. population was within 150 miles of the proposed speedway.

In 1926, Schwab and a group of investors transformed part of the old Amatol munitions plant into a 1.5-mile wooden track designed to attract fans from nearby cities and to compete with established venues like the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. The track, built by Jack Prince’s construction company, was steeply banked and wide enough to handle speeds up to 160 mph, making it one of the fastest racetracks in the world at the time. Schwab aimed to draw thousands of spectators to Atlantic City’s outskirts, using the region’s extensive rail network to bring fans from major urban centers.

The Amatol Bowl – The World’s Greatest Motordrome

A 1 1/2 Mile Wooden Motorsports Speedway

The Amatol Speedway, often dubbed “The World’s Greatest Stadium,” was a massive 1.5-mile wooden raceway that set a new standard in motorsport infrastructure. Constructed in 1926, the speedway featured a 50-foot-wide wooden oval bank that achieved speeds up to 160 mph, requiring over 4.5 million board feet of lumber—enough to fill around 253 railroad cars. In addition to the track, a massive 60,000-seat grandstand was constructed from 1.5 million board feet of lumber. Standing over 75 feet high, this grandstand supported an additional 250,000 standing spectators, creating a truly monumental venue. The Speedway, also called a motordrome, had its grand opening on May 1, 1926, saw over 80,000 attendees, and set six new speed records that day. The venue included significant parking infrastructure to accommodate 60,000 cars and special transportation arrangements such as a newly built “Speedway, N.J.” train station and additional road expansions to handle the crowds.

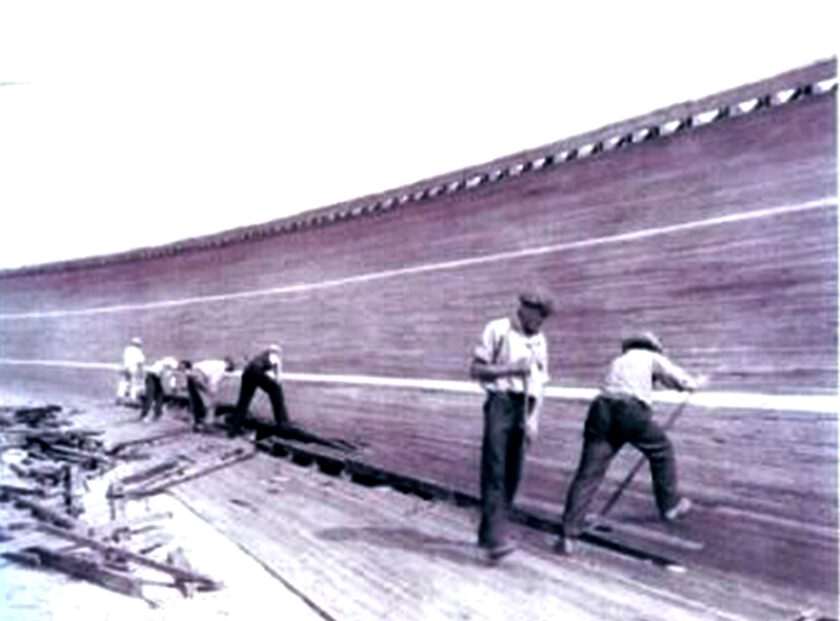

Amatol Motordrome Construction

The Amatol motordrome was approximately 22 miles west of Atlantic City, but the track was often called the Atlantic City Speedway. The Speedway was a unique board track that used approximately 4.5 million board feet of lumber, primarily southern hemlock and white Engelmann spruce.

The Speedway was a unique board track that used approximately 4.5 million board feet of lumber, primarily southern hemlock and white Engelmann spruce. This immense quantity of wood, enough to fill around 253 railroad cars, was necessary to create its steeply banked, 1.5-mile-long, 50-foot-wide racing surface designed for high-speed racing up to 160 mph.

Construction began in early 1926 and finished just a few months later, in time for the track’s opening in May 1926. While the exact number of people involved in building the speedway isn’t specified, the available labor force in the area likely contributed to its construction, especially since the facility repurposed existing infrastructure from the former Amatol munitions plant.

The Amatol Speedway’s track was notable for its steep banking, estimated to be around 45 degrees. This angle allowed cars to maintain higher speeds around the 1.5-mile wooden track, making the races thrilling yet hazardous. The boards were laid on edge, which helped maintain the durability and shape of the track during the high-speed races held there. This kind of construction was a hallmark of the board-track racing era, which saw a brief but spectacular rise in popularity before more durable materials replaced wood in racetrack construction.

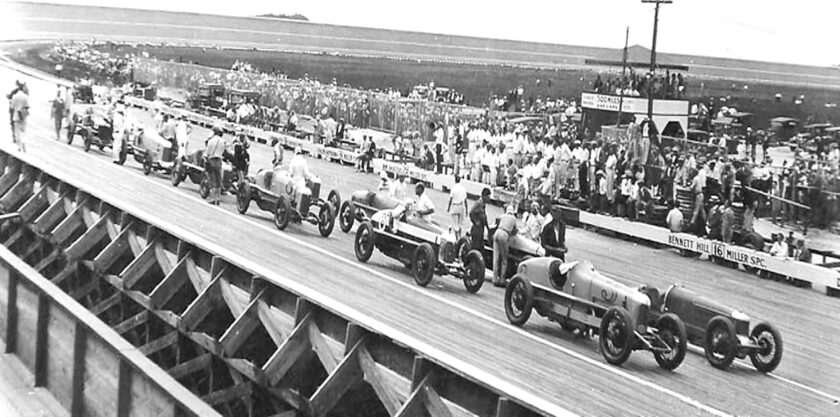

Opening Day- May 1, 1926

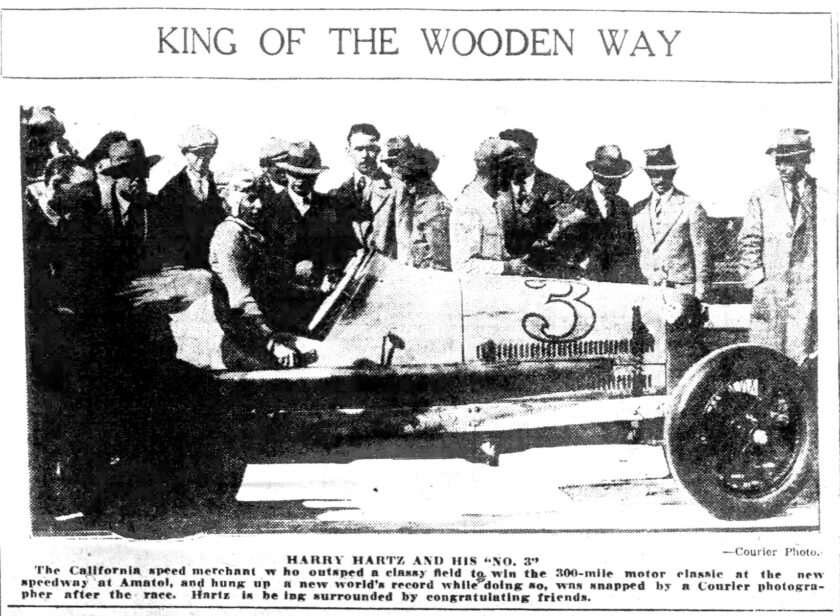

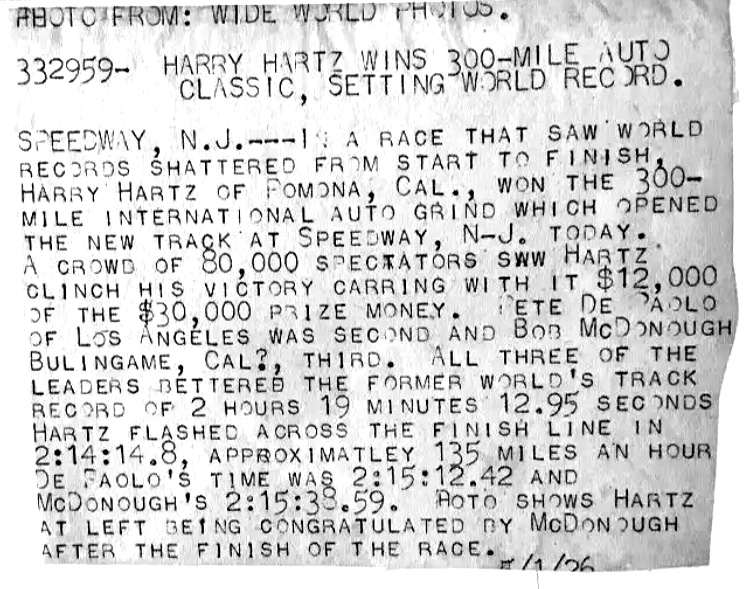

Opening day on May 1, 1926, was a significant American event, drawing over 80,000 spectators eager to experience high-speed racing on the East Coast’s biggest wooden track. The track quickly became a destination for top drivers from across the country. The opening race was a 500-mile challenge won by prominent racer Harry Hartz, setting the tone for the Speedway as a significant attraction. Hartz won the first race at an average speed of 134.091 mph. For a brief period, Amatol rated better (faster) than the Indianapolis 500 motor speedway.

The crowd on opening day was reportedly captivated by the spectacle of cars reaching speeds of over 120 mph, racing on a massive wooden structure designed to thrill audiences. This new venue, set amidst the wooded area near Hammonton in Mullica Township, New Jersey, aimed to create an atmosphere comparable to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, where many of the same drivers competed. The massive event was about the race and highlighted the public’s fascination with modern engineering feats and the thrill of auto racing.

Motorsports Royalty In Attendance

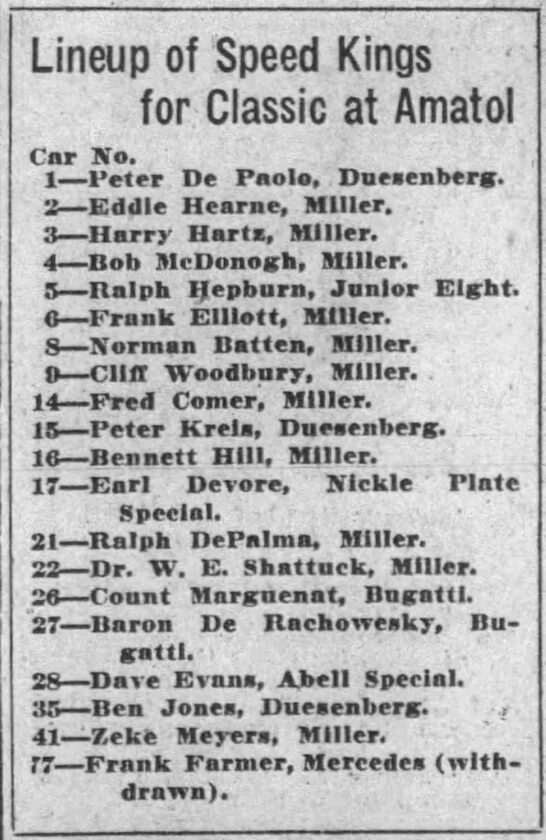

All the big names in motorsports showed up for the inaugural race at Amatol. The drivers of the time included those with deep high-speed experience at places like the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Peter De Paolo, winner of the 1925 Indianapolis 500; Harry Hartz, who finished second in the Indianapolis 500 multiple times; and Eddie Hearne, 1923 AAA National Championship winner.

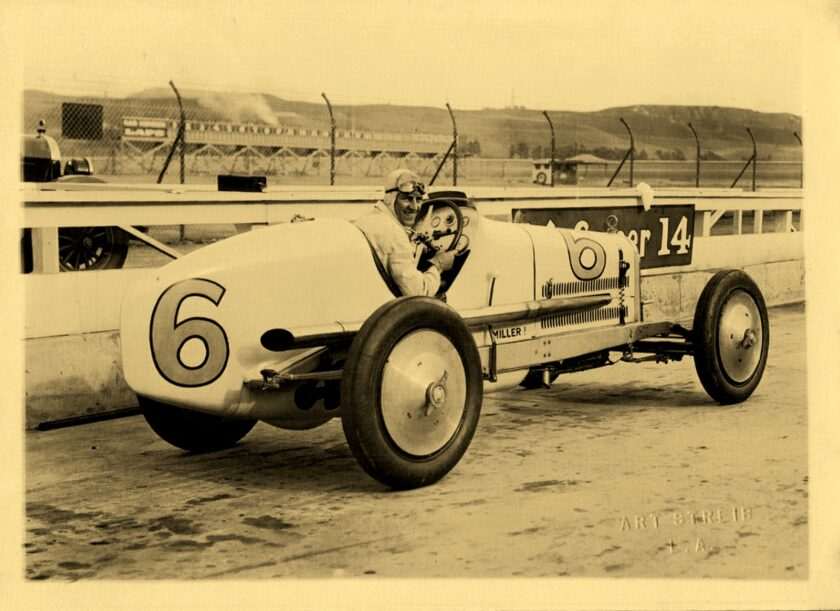

The Racecars

As with many American tracks in the 1920s, some of the most innovative American automobile manufacturers built the top racing cars at Amatol Speedway. Miller, Duesenberg, and Frontenac made notable contributions. These manufacturers were at the forefront of automotive engineering, focusing on performance, speed, and reliability in an era of high-risk, high-reward racing.

The intense demands of board-track racing led to rapid advances in engineering, with manufacturers like Miller and Duesenberg developing technologies that would influence racing for decades. Harry Miller and his Miller race cars were produced in Los Angeles, California, and were arguably the top name in American racing during the 1920s. His cars were advanced for the time, featuring high-performance engines and lightweight designs. Duesenberg, founded by the Duesenberg brothers Fred and August, the Duesenberg company produced high-performance racing cars in Indianapolis, Indiana, that competed closely with Miller’s designs.

Frontenac was the beginning of Chevrolet. The race cars were produced in Indianapolis, Indiana by Louis Chevrolet and his brothers, Arthur and Gaston Chevrolet. Known for their ingenuity, they produced competitive cars, though generally less dominant than Miller or Duesenberg. Frontenac focused on engine upgrades, specializing in modifying Ford Model T engines and enhancing them for racing.

A key component of the car was the tires. The tires used on board tracks were primarily supplied by Firestone and Goodyear. These companies were pioneers in tire manufacturing and played significant roles in developing racing tires during the early years of American motorsports. Tire technology was still developing, so blowouts, punctures, and rapid wear were common problems.

Manufacturers like Firestone were constantly innovating to create tires that could survive the extreme heat and high speeds of board-track racing. However, safety standards were far from what they are today. The tires were generally made from hard rubber compounds with high heat resistance caused by the high heat friction between the wood and the tire’s high rotational speed.

Results: World Records and a Banner Race

Motorcycle Racing Too at Amatol Speedway

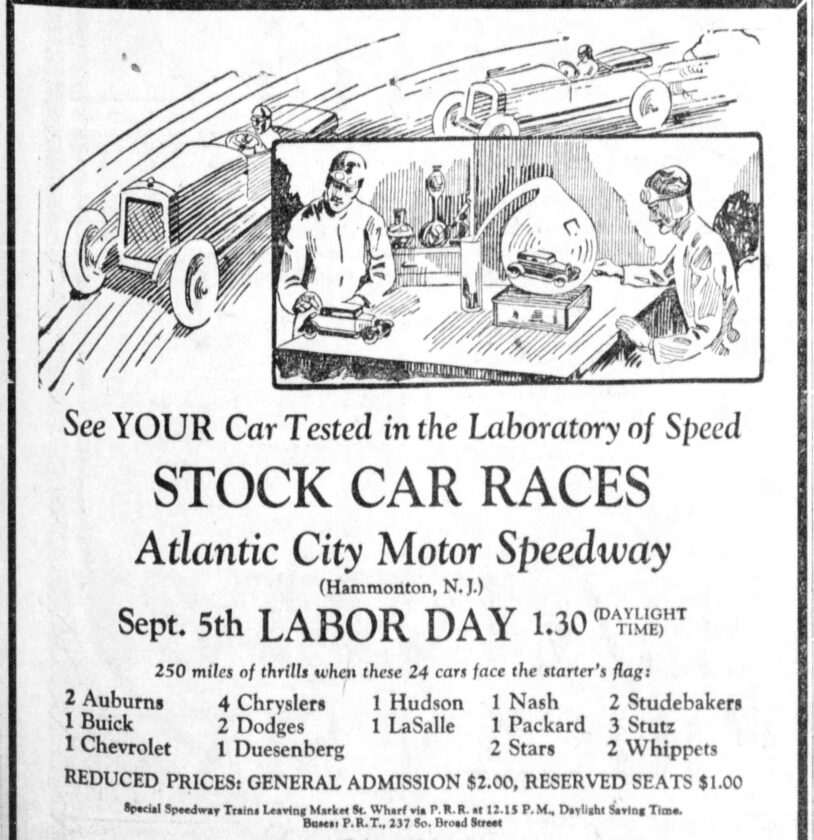

Motorcycles also raced at Amatol Speedway, with events specifically featuring motorcycles alongside stock cars. The final racing event, held on Sunday, September 16, 1928, was an automobile race that ended the season and was also the last race at the track.

Track Struggles

The Amatol Speedway faced several ongoing struggles, contributing to its short lifespan. It closed just two years after opening in 1926. The track was built entirely from wooden planks, requiring constant repairs due to wear and weathering. These wooden board tracks were expensive to maintain and highly susceptible to splintering and breaking under the pressure of high-speed racing. Almost every track constructed from wood only lasted a few years as the wood would erode.

Safety was also a major concern. The design and materials posed severe safety risks for drivers and spectators. The cars raced at very high speeds on steeply banked turns, which, combined with wooden boards, increased the likelihood of accidents. Fatal accidents and injuries were common in board-track racing during that era, deterring some potential racers and audiences.

Financial viability was a big challenge. Although the Speedway attracted large crowds, the profits were insufficient to offset the high maintenance costs and initial investment. Competition from other more established racetracks, like the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, and the high expenses involved in continually repairing the track made it financially unsustainable.

By 1928, the Great Depression began affecting investments in entertainment, and auto manufacturers—initially using the track as a testing ground after the races stopped—sought more modern facilities elsewhere.

1928 – Final Races

They were known as the “Speed Kings” and Motordrom Gladiators, who had avoided death with their record-breaking daredevil antics at the speedway. Motorcycles met for their final gathering on July 4, 1928, while the auto racers met in a 100-mile sprint classic on September 16, 1928.

Sat, Sep 15, 1928 ·Page 26

More Insane “Board Speedways“

I just thought I would share other speedways of the time that were known for initial motorsports speedway racing. This is a fun look. Like other board tracks of the era, AC Speedway and bigger venues like Beverly Hills Speedway had a brief period of popularity before the sport evolved with safer, more sustainable track designs, like Indianapolis Motor Speedway and Daytona Speedway.

Interactive Map

There were 24 board tracks built in the United States for automobile racing that ranged from a half mile in length to the two-mile monsters in Maywood, Illinois; Brooklyn, New York; Cincinnati, Ohio; and Tacoma, Washington. There was a 1/2 mile one in Woodbridge, NJ and a 1 1/2 mile track west of Atlantic City, NJ. Source: Board Tracks Guts, & Glory by Dick Wallen.

Speedway Closing & Demolition

Its final race, won by Ray Keech, was held on May 30, 1928. After the Atlantic City Speedway closed after only two years of operation, the speedway officially closed on September 16, 1928. The track sat dormant for about five years until demolition began in 1932. Its 4.5 million feet of wood boards were repurposed in several ways and spread throughout other South Jersey construction efforts. Initially, parts of the track were used by companies like Studebaker for vehicle testing, but by 1933, the speedway was dismantled. Most of the lumber was sold, though the Hammonton Fire Department later burned any unsold wood to clear the site. The area eventually returned to its natural state.

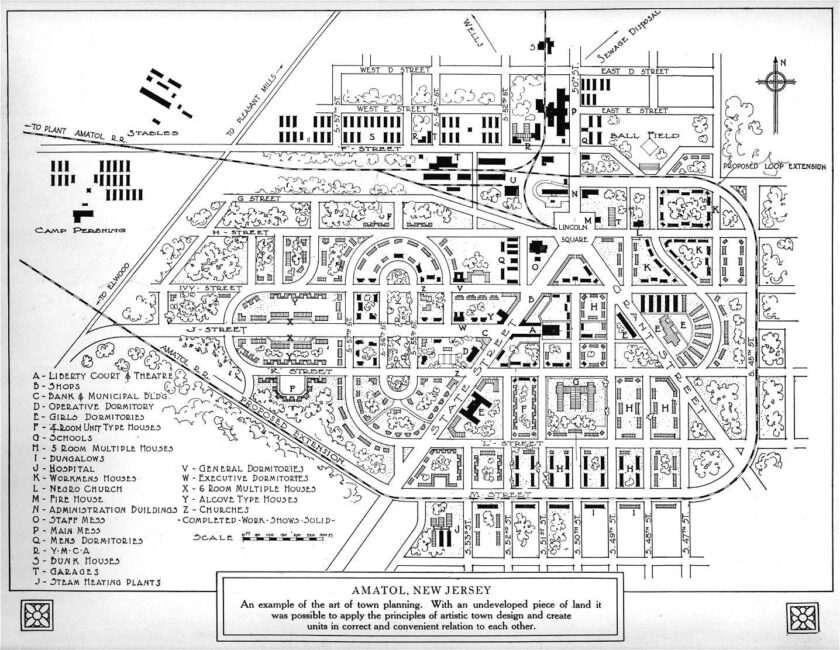

Backstory – Amatol, New Jersey – What is Amatol Anyway?

The Amatol Munitions Plant was a significant World War I facility outside Hammonton in Mullica Township, New Jersey. Established by the U.S. government in 1918 to address the demand for explosives, the plant focused on producing a blend of TNT and ammonium nitrate, known as Amatol, a cost-effective and potent military explosive.

The site, covering about 6,000 acres, was chosen for its relative isolation and ample space. It quickly grew into a bustling manufacturing center for wartime munitions. A purpose-built town called Amatol was developed nearby to house up to 20,000 workers and their families. Then, after the war ended, so did the factory, the town, and the people….. until the track was built!