Mr. Local History researchers are investigating a long whispered local mystery we’ve named “The Missing Marlboro Man.” A man connected to the Marlboro advertising era, tied in some way to Basking Ridge, then seemingly disappearing from the public record. No clear trail. No photos. No confirmed outcome. Just fragments and unanswered questions.

If you have any information at all, wife’s name, nickname, photo, newspaper clipping, modeling card, casting notice, address, workplace, or even a story passed down through family, please share it. Even the smallest detail may matter. You can comment below or drop us a message privately. All leads will be handled carefully and verified before publication. Help bring clarity to one of Basking Ridge’s intriguing stories.

First Possible Marlboro Man – Michael Roscoe from Liberty Corner

We have been hearing this rumor for years and we quietly searched and would often ask local residents if they remembered “The Marlboro Man from Basking Ridge.” Strangely, we wrote a story about the Glider Field atop Schley Mountain and the later development and BOOM, someone shared a clue:

As the Hills took shape in Bedminster and Bernards Township, longtime residents often recall how unexpectedly small the world still felt. One neighbor remembered living along Mt. Prospect Road and noted that just beyond the Moores lived Mike Roscoe and his wife. Roscoe, they recalled, was one of the Marlboro Men, while his wife, was also a working model. It is one of those quiet details that catches people off guard. A national advertising icon tied to wide open Western imagery was, at one point, simply another neighbor in the Somerset Hills, sharing the same roads and routines as everyone else.

By the mid 1960s Michael Roscoe and his wife were established residents of the Mt Prospect Road area in Basking Ridge within Bernards Township living on a property that directly bordered the Good Rod and Gun Club on Mt Airy Road on Schley Mountain in the area of the Schley Glider Field.

The Bernardsville News confirmed that the Roscoes lived on a property that included a pond with at least one outbuilding located near the water. During 1965 township hearings Michael Roscoe testified about what was going on at his neighbor; the Good Time Rod and Gun Club. He testified that he personally removed multiple slugs from his barn structure and believed they originated from shooting at the neighboring gun club.

The property appears to have been large and semi-rural consistent with Mt Prospect Road parcels of the period many of which included water features wooded buffers and secondary structures. This setting helps explain why the Roscoes were viewed as credible primary witnesses when safety concerns escalated.

Mrs. Roscoe played an active role as well. While her first name does not appear in the published article she is documented as reporting verbal harassment and obscene language directed at her by club members as they drove past the property. Her testimony reinforced that the issue extended beyond noise into personal conduct and quality of life. Together Michael and Mrs. Roscoe emerged as leading neighborhood voices helping organize broader resident opposition. A petition signed by 46 residents supported their claims and led to formal Township Committee action. Their involvement was instrumental in the township decision to deny Sunday shooting at the club.

In later years a nearby neighbor, Susan Bush, referred to Michael Roscoe as “the Marlboro Man,” a nickname remembered locally and passed down through neighborhood recollections. She also remembered the Roscoe’s two dogs; Brigette and Baja, both German sheppards.

While no contemporary documentation has yet confirmed a formal advertising role the reference reflects how Roscoe was remembered within the community and helps explain the origin of the long standing Marlboro Man association. But we keep digging.

Second Marlboro Man Rumor – Mr. McNellis from Liberty Corner

Two more local residents have come forward saying they’ve also heard there was a Marlboro Man, but this one is from Liberty Corner. Mr. Local History researchers are exploring whether Liberty Corner resident Mr. McNellis may have been one of the many “real rural men” used in Marlboro advertising during the peak years of the campaign. Families across the country are only now uncovering these connections decades later. Mcnellis was a Mountain Road resident who’s family lived down by the known devil tree on a large farmlike property.

Brief History:

The Early Years of the Marlboro Man

When the Marlboro Man first appeared in the early 1950s, he was not the rugged cowboy most people picture today. Marlboro cigarettes were originally marketed with a softer image and even promoted as a filtered cigarette that appealed to women. That changed as smoking habits shifted after World War II and filters became more common among men. Advertisers needed a way to make filters feel tough, masculine, and unmistakably American. The solution was to reinvent the brand’s identity around strength and independence.

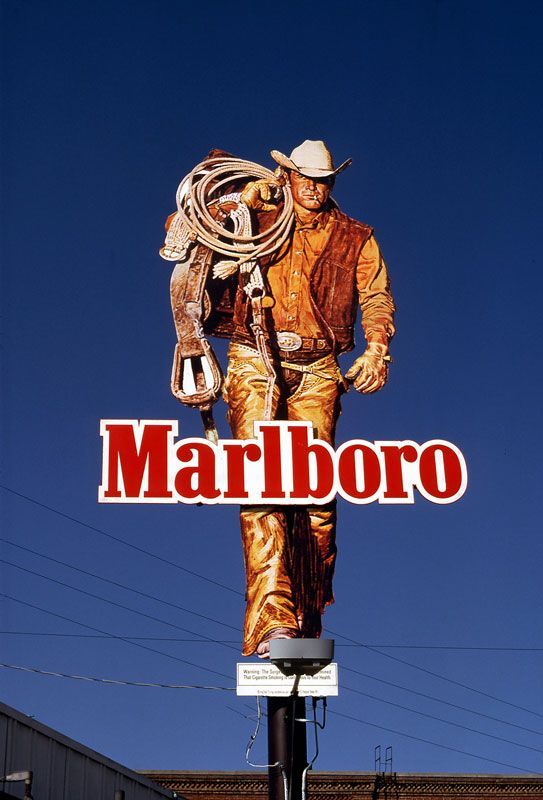

Early Marlboro Man ads featured a range of masculine figures including sailors, construction workers, and ranch hands. Over time, one image rose above the rest. The cowboy. Set against wide open landscapes, the cowboy embodied self reliance, quiet confidence, and a life lived on one’s own terms. He rarely spoke. He did not explain himself. He simply existed in a world of dust, leather, horses, and open sky. That silence was part of the power. The Marlboro Man became less of a salesman and more of a symbol, a visual shorthand for freedom at a moment when postwar America was redefining masculinity.

Marlboro Man in More Recent Advertising History

By the 1960s and 1970s, the Marlboro Man was one of the most recognizable advertising figures in the world. His image dominated billboards, magazines, and later television, helping Marlboro become the top selling cigarette brand in the United States. The campaign barely changed because it did not need to. New cowboys came and went, often real working ranchers, but the message stayed the same. Independence. Grit. An unspoken promise of authenticity in an increasingly modern and crowded world.

As public awareness of smoking related health risks grew, the Marlboro Man took on a more complicated legacy. By the 1990s, restrictions on tobacco advertising removed him from television and many public spaces. The character faded from view, but not from memory. Today, the Marlboro Man is often discussed less as a pitchman and more as a case study in how powerful imagery can shape culture. He remains one of the most successful branding creations ever, a reminder of an era when advertising could create a myth so strong that it felt real, even long after the billboards came down.

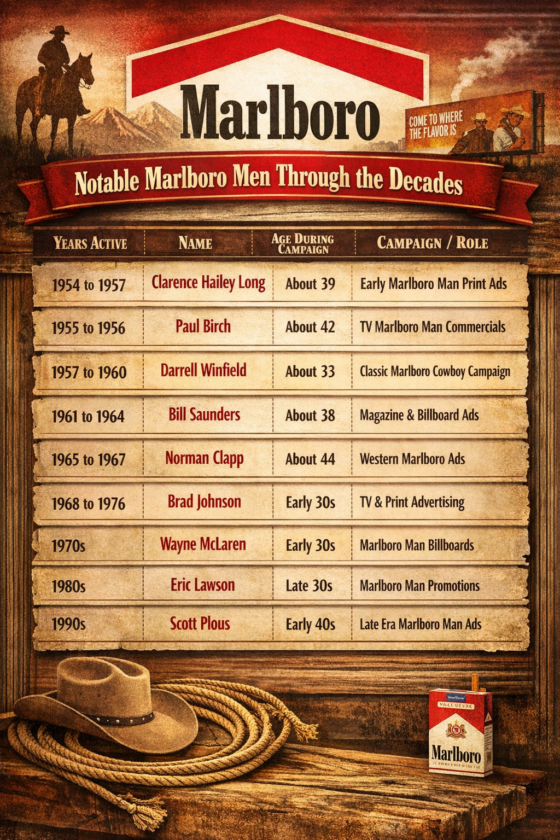

Marlboro – The Men & How They Tried to Come Clean

Marlboro rarely credited its models publicly, and multiple men often appeared simultaneously under the single identity of the Marlboro Man. The power of the campaign came from consistency of image rather than celebrity recognition, making the cowboy feel timeless rather than tied to any one individual.

When people talk about the darker side of the Marlboro Man, one name always comes up first, and for good reason. Wayne McLaren was one of the few men who not only appeared in the ads but later publicly confronted what smoking had done to him. After developing lung cancer, McLaren became an outspoken critic of the tobacco industry. He testified, appeared in public health campaigns, and warned others that the cigarettes he once promoted had cost him his health and his voice. His death at age 51 in 1992 turned him into a powerful and very human counter image to the invincible cowboy persona Marlboro had spent decades building.

Another former Marlboro Man who later acknowledged the dangers of smoking was Eric Lawson. Lawson appeared in Marlboro advertising during the 1970s and 1980s and later suffered from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In his later years, he spoke openly about how long term tobacco use had damaged his lungs and supported efforts to reduce smoking. While his story received less attention than McLaren’s, it reinforced the growing public understanding that even the strongest looking advertising symbols were not immune to real world consequences.

At the same time, it is important to separate documented history from popular myth. Several other men who portrayed the Marlboro Man, including Darrell Winfield, Clarence Hailey Long, and Paul Birch, did not die of smoking related cancer and did not publicly campaign against tobacco. Over time, a simplified narrative took hold suggesting that most Marlboro Men met the same fate, but the historical record shows a more complicated reality. What endures is not a single outcome, but a lesson in how powerful advertising imagery can shape belief, and how real lives eventually reveal the limits of even the most carefully constructed myths.