Television executives have always known people have an obsession with true crime. It is quite possible that this obsession can trace its roots back to an unfortunate event that occurred in Somerset County. On the night of September 14, 1922, a New Brunswick church rector named Edward Hall and a churchgoer named Eleanor Mills were murdered in a rural field just over the Somerset County border. Many unique events were sensationalized by media coverage and legal proceedings. Some have called this the first “trial of the century” due to its heightened newspaper coverage and public intrigue. Arguably, never before had a trial attracted this much public attention.

The People and the Crime

Edward Hall was an Episcopalian church rector who was originally from Brooklyn. He obtained a theological degree in Manhattan and served different churches in the borough during his early career. In 1909, he began his tenure at St. John’s Church in New Brunswick, but not before briefly serving in Basking Ridge or Bernardsville. Hall was well respected in the church but had a personal shortcoming. He had an ongoing affair with a frequent churchgoer named Eleanor Mills for at least two years.

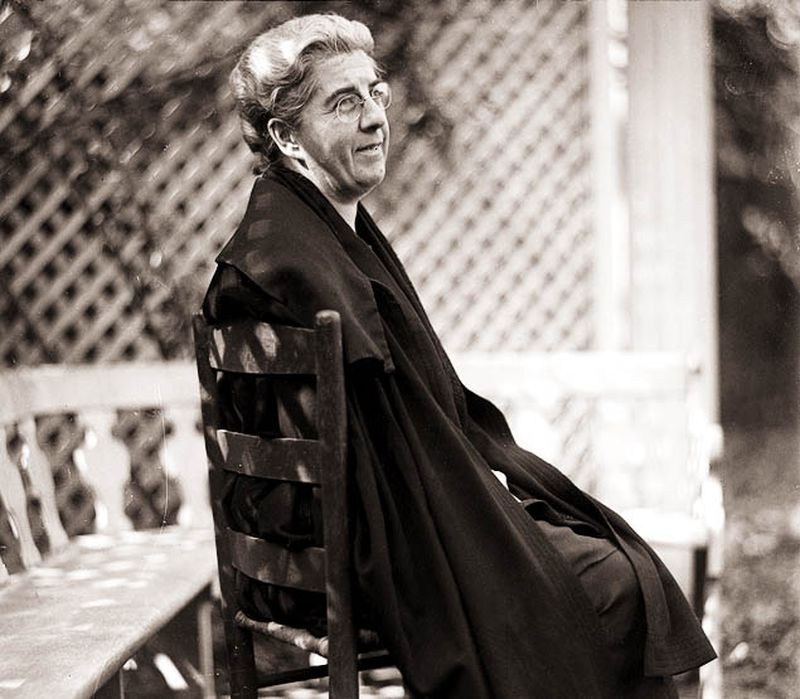

Edward was relatively well off and married to Frances Hall, née Stevens, from the prominent New Jersey Stevens family. Through Frances’ mother and aunt, she was also an heir to the Johnson surgical supply fortune. Eleanor Mills, by contrast, came from a lower middle-class background and was married to James Mills, a shoe-maker turned church custodian. Both respective spouses and at least some of the other congregants knew about the affair. There was even evidence of love letters passed to one another in hymnals. On the night of September 14, 1922, the two left their respective residences, never to be seen again.

For two more nights, both Frances Hall and James Mills waited in anxiety, as both of their spouses had not returned and had not been seen. It was then, on the morning of September 16th, that passersby Clifford Hayes and Pearl Bahmer accidentally discovered the two bodies. Both Edward Hall and Eleanor Mills were found dead using gunshot wounds and, in the case of Eleanor Mills, an additional laceration in the throat. The crime scene was a field on a farm over the border into Somerset County, dubbed a well-known “lovers lane.” Subsequently, an investigation with very few leads was undertaken. The perpetrator(s), motive, and even the location of the crime all had to be found from just a tiny amount of evidence.

The Rise of Tabloids and Their Influence on the Investigation

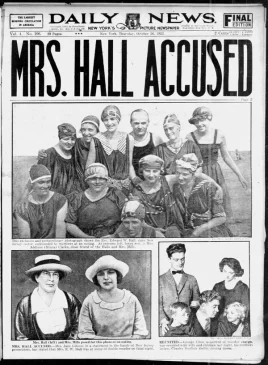

When the trial went public, rumors had abounded in the local community, but rumors also swirled extensively nationally. The first United States-based tabloid newspapers were printed only a few years earlier. These tabloids focused on intrigue rather than facts and would popularize the case to a broader audience. The New York Daily News and the New York Daily Mirror were the largest tabloids at the time. Soon after the crime was reported, many newspaper reporters and private citizens rushed to the crime scene daily. Unfortunately, the scene was constantly mobbed and became more of a spectacle, lacking respect for the victims. In the weeks that followed, the ground was repeatedly trampled. Vendors hawked balloons and soft drinks every day during the investigation. The New York Times reported a year later that tens of thousands took souvenirs from the surrounding landscape. The commotion probably caused evidence to be distorted or maybe destroyed, as police and investigators did little to stop the visitors at the scene. The subsequent oddities of the investigation would keep the tabloids and the public intrigued throughout the case.

The investigation was led by two prosectors, one from Somerset County and the other from Middlesex County, as it had not yet been determined where the actual crime was committed. Separately, the rival prosecutors found nothing after two weeks, so they were compelled to work together to present suspects to the grand jury. The initial suspect was passerby Clifford Hayes, who himself was having an affair with the girlfriend of his friend Raymond Schneider. Maybe out of spite, Hayes’ accuser was Schneider. However, Raymond Schneider reportedly was known to be a serial liar. So much so that a justice fund was created by the local community in defense of Hayes. Sure enough, Schneider confessed a few days later that his accusation was a lie. Soon after, various other people who lived in New Brunswick claimed to have been aware of leads or heard noises that they claimed were connected with the murder. These claims had some inconsistencies or didn’t match up with other facts, leading to many dismissed immediately. It was back to square one, as the lack of leads in the case required a special prosecutor to be appointed in mid-October 1922.

Amidst the scattered testimony from supposed witnesses, a possible true eyewitness emerged, a farm worker named Jane Gibson. The eccentric Jane Gibson claimed she saw Edward’s wife, Frances, her two brothers, and a cousin at the scene of the murder. She claimed that she saw and heard the murders while she was staking out, trying to catch corn thieves. However, that night, Frances Hall, her two brothers, and her cousin had alibis about their whereabouts. The prosecutors also reported that Gibson kept changing her story. Finally, testimony from friends and townspeople challenged Gibson’s story. After several weeks of investigation, with sixty-seven people probed for questioning, the grand jury decided not to convict anyone. The case seemed to have been put to rest if not for the continuing interest of the tabloid press.

Sensationalism and the Case Re-Opening

The combination of public interest and the multitude of tabloid articles about the murder prevented the case from being completely closed. Even non-tabloid publications such as The New York Times, in a September 9, 1923 article, called it “a mystery that commanded international interest.” The same article went on to fully detail the lives of the victim’s family members. This included Frances Hall, her brothers Henry and William, James Mills, and James’ daughter Charlotte (who had her theory about the murders). The article reads like a tabloid, focusing more on the character of each person rather than biographical information. Actual tabloid papers like the New York Daily Mirror, New York Daily News, and New York Graphic ran stories about the murders that were sensationalized to an outrageous degree. The New York Daily News staged a seance at the scene of the murders using a fake medium. The New York Daily Mirror sent one of its reporters to New Brunswick to scavenge for witnesses, even those that were misleading. Additionally, each tabloid paper had no shame in continuously publishing pictures of the victims, family members, and their properties.

These tabloid papers not only renewed public interest in the case but also played a major role in its legal re-opening. The case was reopened in September 1926, almost four years after the grand jury’s decision. The catalyst was the husband of a former maid of the Halls, who filed a petition for annulment of his marriage. He filed the annulment because his wife supposedly withheld knowledge of the Hall-Mills case. He claimed on the night of the murder that Frances Hall, Willie Stevens (Mrs. Hall’s brother), and his wife drove to the field to intercept Hall and Mills.

Additionally, he claimed his wife was given $5,000.00 to keep quiet. As soon as this story broke, the tabloid newspapers went wild with embellishments of the new details. As a result, Frances Hall, her two brothers, and a cousin, Henry Carpender, were arrested.

The new Hudson County-based special prosecutor inherited a giant mess. Masses of evidence had vanished in the four years in between investigations. It also became apparent that the Somerset County prosecutor in 1922 had systematically mislaid vital evidence. The previous prosecutor’s brother was also caught trying to sell grand jury testimony to a tabloid newspaper. All four defendants were eager to speak to the press and proclaim their innocence.

The Trial

After establishing that the murder was not committed somewhere else and moved, a Somerset County grand jury indicted Frances Hall, Willie Stevens, Henry Stevens, and Henry Carpender. The latter was to be tried separately, while the three other defendants’ trial started on November 6, 1926, in the Somerville courthouse. The prosecutor argued that Frances’ motivation was to catch her husband in the affair with her brothers assisting her. A crucial piece of evidence was Edward Hall’s calling card, which contained Willie Stevens’s thumbprint. An early key witness was Ralph Gorsline, an assistant manager for one of the companies owned by the defendants’ family. He claimed to have heard shots on the scene (while participating in an affair of his own), something he had previously denied. Gorsline also claimed that Willie Stevens threatened him and that Henry Stevens bribed him. Other witnesses claimed to have seen Henry Stevens in the area when Henry claimed he was in Lavalette. These witnesses also claimed that Frances Hall tried to bribe them, discrediting the defendants’ alibis. However, according to the press and some of the public at the trial, none of these witnesses, including the accusatory maid’s husband, were credible.

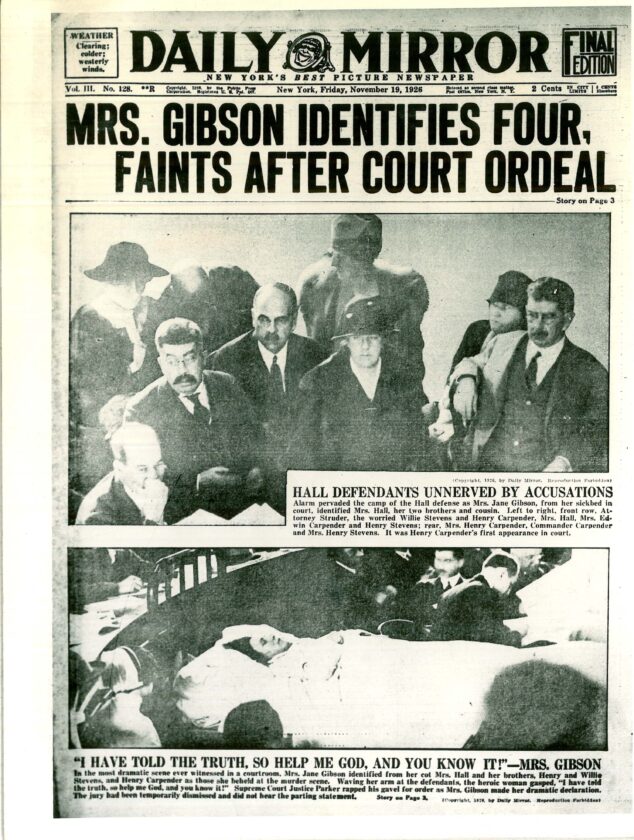

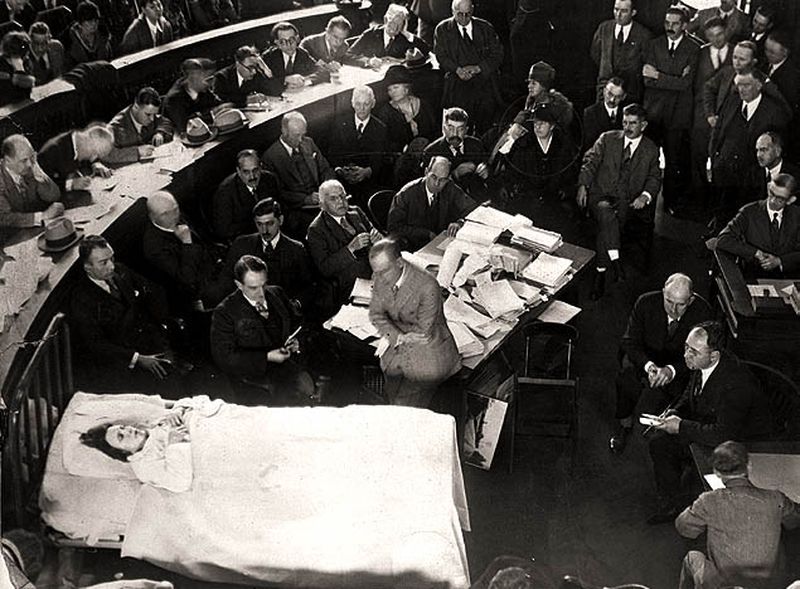

One week into the trial, the prosecution called its star witness, Jane Gibson. The quirky Gibson’s story was discredited by a grand jury four years earlier, but the tabloids found her fascinating, dubbing her “the pig lady.” The new prosecutors believed her accounts were accurate. Gibson arrived at the courtroom to take the stand on a hospital bed, sick from cancer. While Gibson was authentically ill, she didn’t spare the dramatics during her testimony. When asked by the prosecution to point out the perpetrators, she theatrically rose from her bed and sharply pointed her finger toward the defendants. An issue of The New York Daily Mirror from November 19, 1926, called it “the most dramatic scene ever witnessed in a courtroom.”

Despite suffering from a harsh ailment, there was no sympathy for the woman dubbed “the pig lady.” Neighbors and acquaintances later claimed that Gibson was a serial liar. A New York Times article three years earlier stated that a civilian bribed her $100 for corroboration. Even Gibson’s mother repeatedly murmured to herself throughout the testimony that her daughter was lying. The defense would later call on Gibson’s mother to attack her daughter’s character. The prosecution’s reliance on Gibson as the star witness against Frances Hall and her two brothers backfired immensely.

A couple more bombshells were dropped against the prosecution’s case. Soon after the Jane Gibson fiasco, the brother of the late prosecutor from the original 1922 case marched down the courtroom aisle carrying alleged missing documents. These documents further muddled the case, as the state had been unable to find them since the case was reopened. Then, George Totten, a witness called by the defense, admitted that after being discharged as a detective with Somerset County, he was employed by the New York Daily Mirror tabloid to get information about the case.

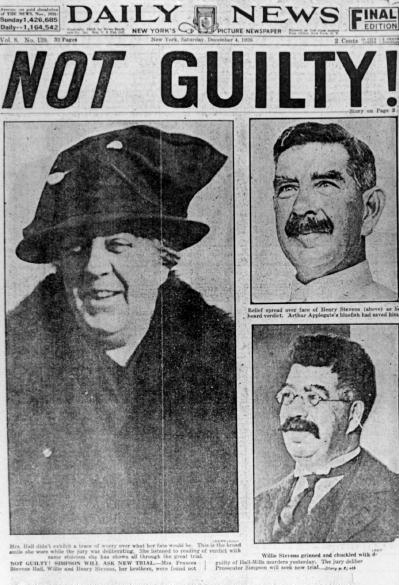

Finally, Frances Hall and her two brothers would take the stand and, in contrast to the prosecution, won over the jury with their succinct story and sincere tone. After a very short deliberation, Frances Hall, Willie Stevens, and Henry Stevens were all acquitted of murder. To this day, the crime remains unsolved.

Interest Continues Decades Later

Even though the case was legally closed on December 3, 1926, interest and rumor continued in the years after the trial. The first major post-trial occurrence was a civil suit brought against Frances Hall in 1928 for a breach of contract by Aaron Blattman, a fingerprint expert. Frances and her brothers asserted that they had never met with Blattman and that the civil case had eventually been dropped. That same year, in April, a man named Elwin F Allen from El Reno, Oklahoma, confessed that he was the murderer. Allen’s affidavit said he murdered Hall and Mills for $5,000 and a car. However, little to nothing substantiated these claims, and the case was not pursued further. In the next decade or so, newspapers across the country, such as the Urbana Daily Courier on October 24, 1932, published “Where are They Now” kinds of articles detailing the defendants and the victims’ family members. The Urbana newspaper article also stated that strangers still often stop and stare at the gates of Frances Hall’s home.

Interest in the case continued in the subsequent decades. In 1964, famed civil rights attorney William M. Kunstler published a book dedicated to the case entitled, “The Minister and the Choir Singer.” He called the case “the most bungled murder mystery in modern times.” Like other publications, his book highlighted the events and sensationalism surrounding the case, but he also offered some unique findings. When researching his book, Kunstler found calendar leaves in a cardboard box in the Somerset County prosecutor’s office at that time. The leaves were wrapped in a piece of crumbling paper that bore the signature of James Mason, the chief investigator in 1922. One of these leaves was in Jane Gibson’s hand during the trial. Kunstler also mentioned an out-of-the-box theory that the KKK was responsible for the murders due to their stance on infidelity. The book was a massive success, getting rave reviews in publications like the New York Times.

Some fascination about the case still exists in the present day. The advent of true-crime podcasts led to the Halls-Mills murders getting a 20-episode season devoted to its events on the true-crime podcast Thinkery and Verse. Understandably, The church of St. John the Evangelist, where Edward Hall was the rector, didn’t want to draw any attention to the incident for many years. However, the church suddenly embraced the events in 2019, when they sponsored and hosted the play “Thou Shalt Not,” a re-enactment of the events and aftermath surrounding the murder. The church in New Brunswick even had a revival of the performance in 2022, this time with Vanity Fair writer Joe Pompeo advertising his book about the murder “Blook and Ink: The Scandalous Jazz Age Double Murder that Hooked America on True Crime.” The 2022 version of the performance ran for nearly a month. Despite being over a hundred years old and possibly overshadowed by subsequent higher-profile cases, the Halls Mills murder still attracts a fair amount of public interest.

The media has extensively covered many high-profile trials in the last two centuries. However, the first one to fit this description happened in Somerset County. It may be argued that the modern fascination with true crime can be traced to this trial.

I don’t understand why the majority of people dismiss the KKK theory out of hand. To me it makes the most sense and I’m pretty convinced of it. There was too much symbolism in the way Mrs. Millls’s body was treated and the way both bodies were posed after death, as well as the placement of the business card and the love letters, for it to be anyone other than the KKK.