The Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. It was engrossed on parchment, and on August 2, 1776, delegates began signing it.

Jefferson drafted the statement between June 11 and 28, submitted drafts to Adams and Franklin, who made some changes, and then presented the draft to Congress following the July 2nd adoption of the independence section of the Lee Resolution. The congressional revision process took all of July 3rd and most of July 4th. Finally, in the afternoon of July 4th, the Declaration was adopted.

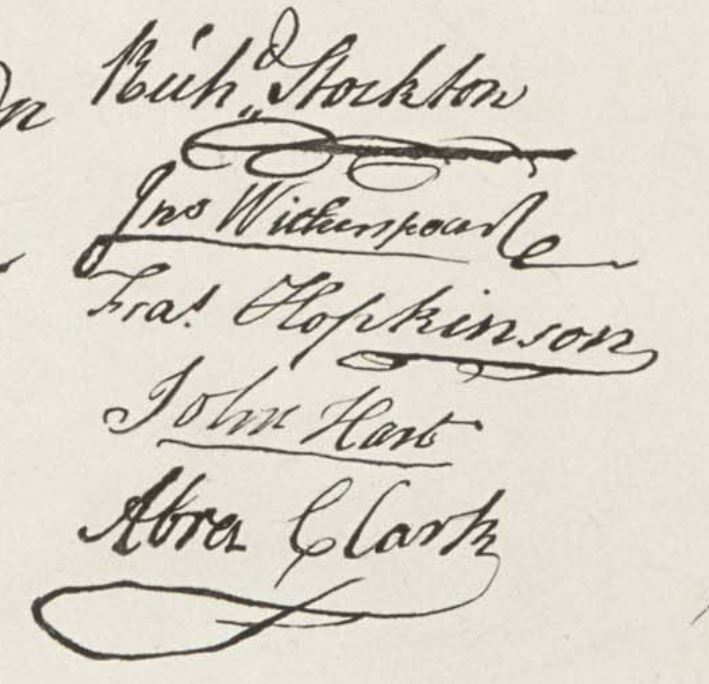

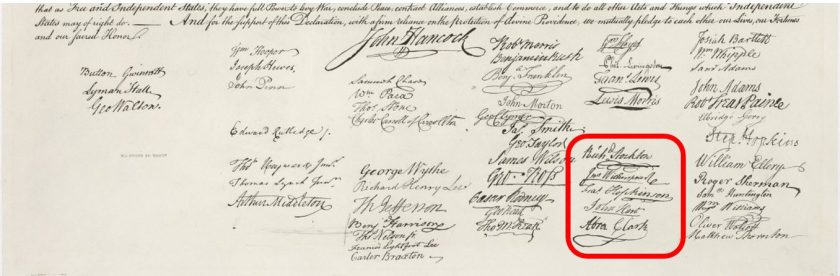

On August 2nd, John Hancock, the President of the Congress, signed the engrossed copy with a bold signature. The other delegates, following custom, signed, beginning at the right, with their signatures arranged by state, from the northernmost New Hampshire to the southernmost Georgia.

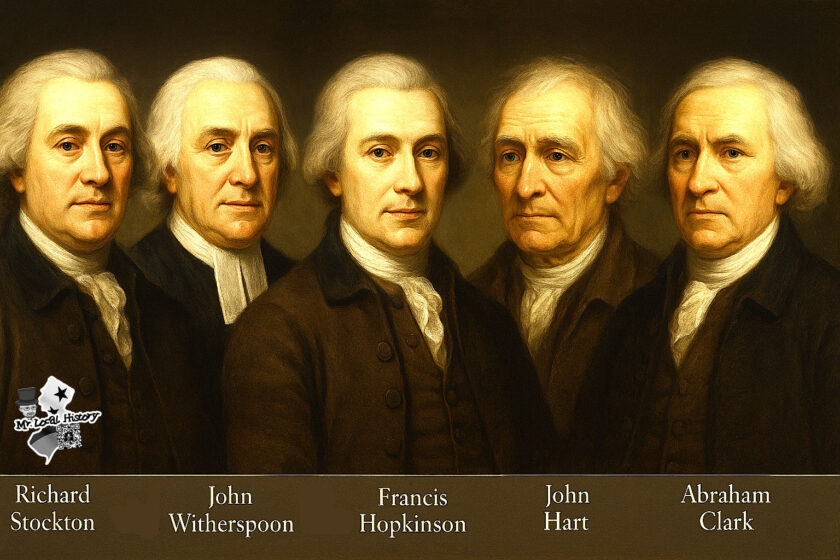

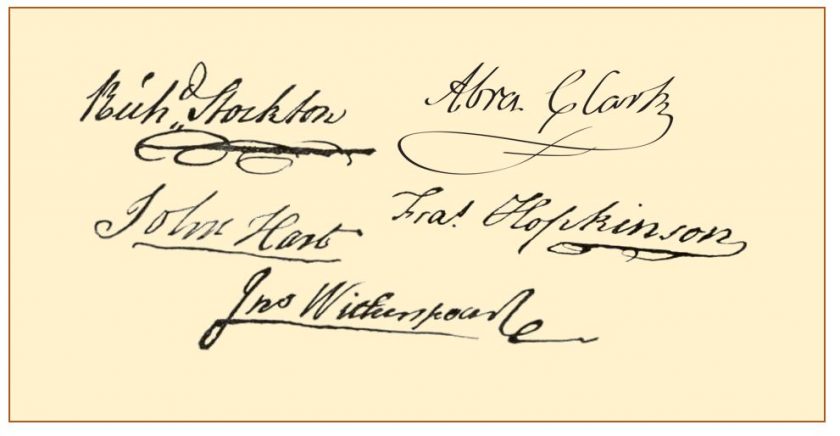

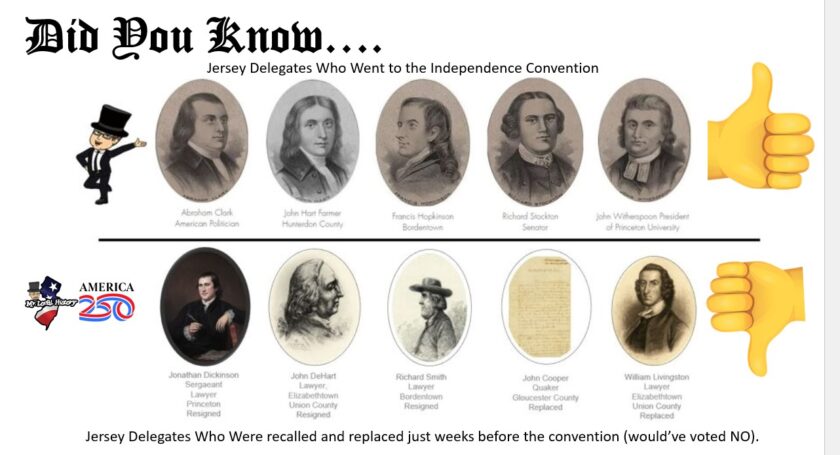

Welcome to the “Jersey Five” of the fifty-six signers of the Declaration of Independence.

- Richard Stockton (Princeton)

- John Witherspoon (Princeton)

- Francis Hopkinson (Bordentown)

- John Hart (Hopewell Township)

- Abraham Clark (Elizabethtown/Rahway)

Declaration of Independence Signing Order and the Dreadful “Smeared Signature”

There is some truth to the idea that the signers of the Declaration of Independence may have followed a methodical order to avoid smudging each other’s signatures. However, this is based more on tradition and inference than on documented instruction. The official engrossed (handwritten) copy of the Declaration was signed primarily on August 2, 1776, not on July 4, and the signatures were generally grouped by state delegation rather than placed randomly.

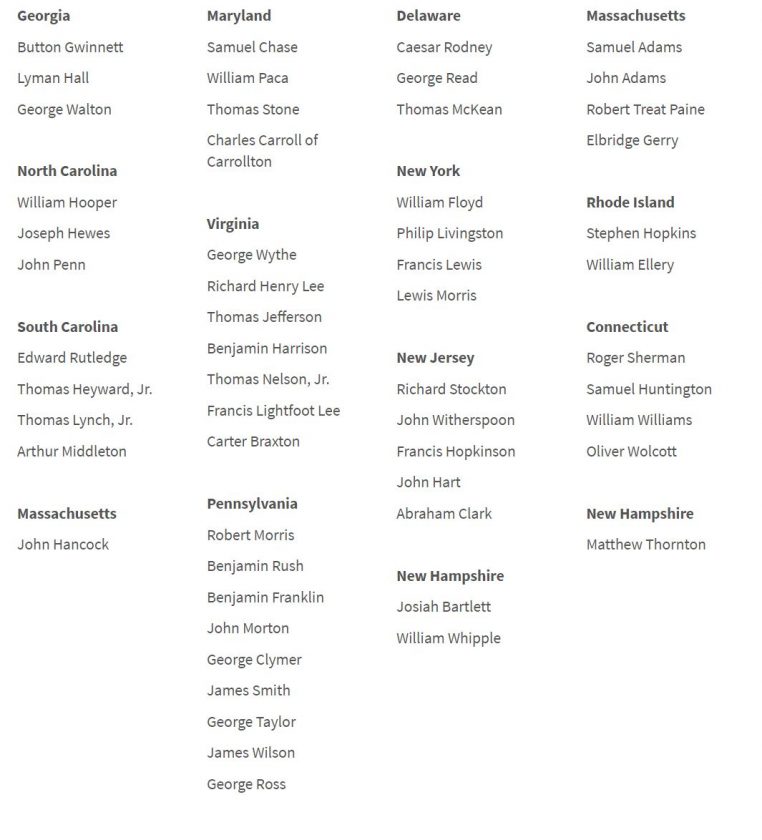

The signers’ order on the Declaration was not alphabetical, but instead followed a general geographical progression by state, beginning with the northernmost states and moving southward in the following order: New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, with John Hancock signing first at the top as President of the Continental Congress.

s there More then One Declaration of Independence?

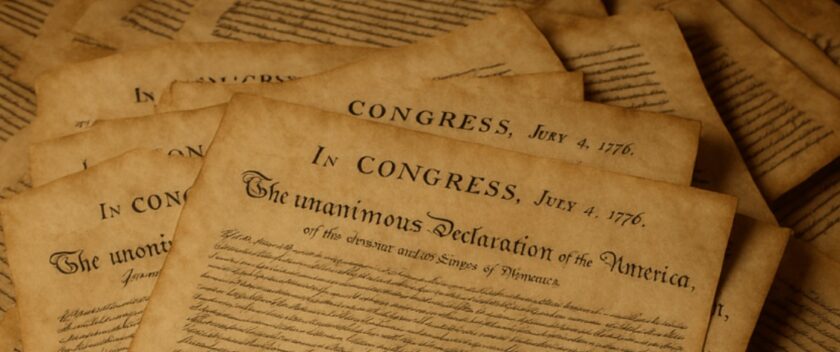

There is only one original, signed, engrossed parchment copy of the Declaration of Independence. This is the formal handwritten version, signed primarily on August 2, 1776, by 56 delegates and now preserved at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

However, multiple versions of the Declaration were produced in 1776 for distribution and dissemination. On the night of July 4, 1776, printer John Dunlap created about 200 copies known as the “Dunlap broadsides.” These were the first printed versions, used to disseminate news of independence to the colonies, the Continental Army, and newspapers. Only about 26 Dunlap broadsides are known to survive today. Other early printed versions were created in the months that followed, such as the Goddard broadside of January 1777, which was the first to list all the signers’ names. These printed editions are historically significant, but are not considered original in the sense of being the signed manuscript.

New Jersey Delegation Debacle

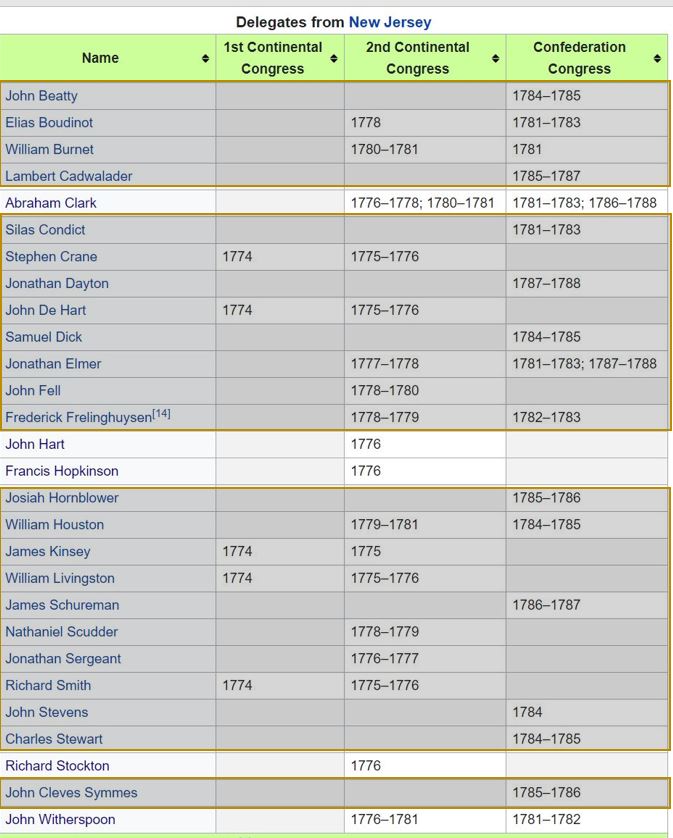

Early in 1776, while New Jersey was divided on the issue of separation, heated discussions took place between the Patriots and the Loyalists. As the issue escalated, the New Jersey state convention replaced all its delegates with those who favored separation. The entire delegation was replaced. Richard Smith, John DeHart, and Jonathan Dickinson Sergeant resigned. Quaker John Cooper had never attended, and William Livingston was too moderate at that moment.

(Alphabetical) New Jersey signers of the Declaration of Independence – 5 of the 56 signatures from each of the 13 colonies. The Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, with 12 of the 13 colonies voting in favor and New York abstaining.

On June 21, 1776, New Jersey appointed a delegation that included a sheriff, a politician who preferred poetry and songwriting to the law, a preacher, a South Jersey farmer, and an associate justice of the state’s Supreme Court. They were: Abraham Clark of Rahway, who was 50 years old; Francis Hopkinson of Bordentown, who was 38; John Witherspoon of Princeton, 53; John Hart of Hopewell, 65; and Richard Stockton of Princeton, 46. The Representatives from the 13 colonies would arrive in Philadelphia on June 28, 1776, and the first vote for the Declaration of Independence took place on July 2, 1776.

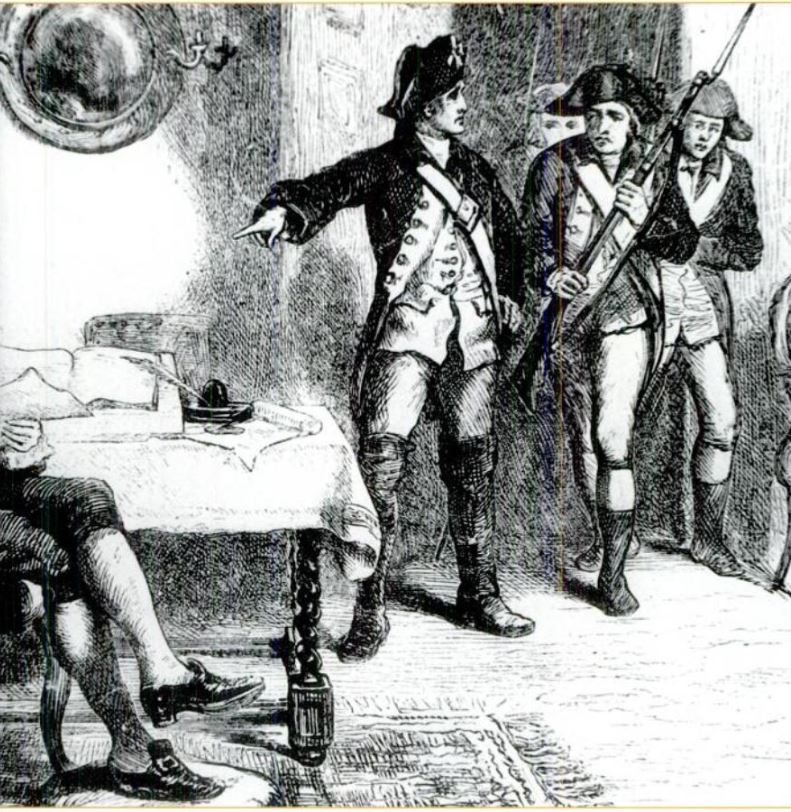

The Provincial Congress then arrested Royal Governor William Franklin (Ben’s son) at the Governor’s Proprietary House in Perth Amboy and voted to replace the New Jersey delegation. Abraham Clark was highly vocal in his opinion that the colonies should have their independence, so he became one of the chosen five.

Get yours today

Attending that June 21, 1776, vote in Burlington representing New Jersey included:

- Jonathan Dickinson Sergeant

- John Witherspoon

- Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh

- James Linn

- Frederick Frelinghuysen

- William Paterson

Richard Stockton – Princeton, New Jersey

Represented New Jersey at the Continental Congress. Princeton (Mercer County).

Richard Stockton was appointed to the Royal Council of New Jersey in 1765 and remained a member until the government was reformed. Richard was the son of John Stockton (1701–1758). This wealthy Princeton landowner donated land and helped establish what is now Princeton University (then known as the College of New Jersey, located in Newark) in Princeton, New Jersey. Richard was born at the Stockton family home, now known as Morven, in the Stony Brook neighborhood of Princeton, New Jersey.

Stockton (and Witherspoon) were elected to Congress to replace two other members after New Jersey learned that the delegates were against independence. Stockton, along with his friend, Witherspoon, signed the Declaration of Independence. Stockton was the first to sign for New Jersey.

Stockton, when captured by the British, was intentionally starved and subjected to cold weather. After nearly five weeks of abusive treatment, Stockton was released on parole; his health was battered. He returned to his estate, Morven, in Princeton, which General Cornwallis had occupied during Stockton’s imprisonment. All his furniture, household belongings, crops, and livestock were taken or destroyed by the British. His library, one of the finest in the colonies, was burned.

Stockton was buried in Stony Brook Quaker Meeting House Cemetery (470 Quaker Road, Princeton), where a marker in his memory is located instead of a modern gravestone.

Abraham Clark – Roselle, NJ

Abraham Clark – Two of Clark’s sons were officers in the Continental Army. He refused to speak of them in Congress, even when they both were captured, tortured, and beaten. However, there was one instance when Clark did bring them up, and that was when one of his sons was put on the prison ship, Jersey, notorious for its brutality. Captain Clark was thrown in a dungeon and given no food except that which was shoved through a keyhole. Congress was appalled and made a case to the British, and its conditions were improved. The British offered Abraham Clark the lives of his sons if he would only recant his signing and support of the Declaration of Independence; he refused.

Clark remained in the Continental Congress through 1778, when he was elected as Essex County’s Member of the New Jersey Legislative Council. New Jersey returned him twice more, from 1780 to 1783 and from 1786 to 1788.

Clark’s old property at 101 West Ninth Avenue in Roselle is open one day each fall as part of Union County’s Four Centuries in a Weekend home tour. The Union County town of Clark is named for the signer, who is buried with his sons in nearby Rahway Cemetery (1670 Saint Georges Avenue, Rahway). Look for a 10-foot-tall obelisk engraved with the signer’s name.

John Hart – Hopewell Township, New Jersey

John Hart – When New Jersey formed a revolutionary assembly (or provincial congress) in 1776, he was elected to it and served as its Vice President. Before June 1776, the New Jersey delegation in the First Continental Congress was opposed to the idea of independence. As a result, the entire delegation was replaced, and Hart was one of those selected for the Second Continental Congress. He joined in time to vote for and sign the Declaration of Independence.

He served until August of that year, then was elected Speaker of the newly formed New Jersey General Assembly.

Hart’s house and farm were probably plundered or damaged, but he wasn’t ruined. A year and a half after his runaway adventure, Hart generously hosted George Washington at his place and allowed 12,000 of the general’s troops to camp in his fields. His grave is marked by an obelisk in the First Baptist Church Cemetery, located on West Broad Street in Hopewell. The tombstone incorrectly reports the date of Hart’s death as 1780. He died in 1779.

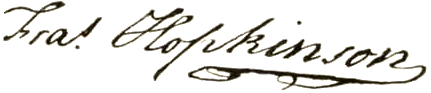

Francis Hopkinson – Bordentown, New Jersey

Francis Hopkinson lived at 101 Farnsworth Street in Bordentown, Burlington County, New Jersey, United States. Built in 1750, it was the home of Francis Hopkinson (1737-1791), the designer of the United States Flag and a signer of the United States Declaration of Independence. He lived in this home with his wife, Ann Borden (1747-1827), from 1774 until Hopkinson died in 1791. Ann Borden was the granddaughter of Joseph Borden, the founder of Bordentown, New Jersey. The house was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1971.

After signing the Declaration of Independence, Hopkinson later designed the first official flag of the new nation.

His house is at 101 Farnsworth Avenue, Bordentown. Occupied by various businesses today, it’s partially open to the public and includes wall displays in tribute to the signer. Hopkinson, who died in 1791 at age 53, is buried at Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia.

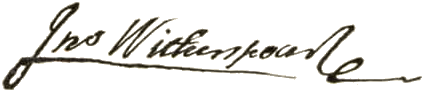

John Witherspoon – Princeton, New Jersey

John Witherspoon brought some impressive credentials and a measure of public acclaim with him when he joined the colonies in 1768 as president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton). Witherspoon was a highly active member of Congress, serving on more than 100 committees throughout his tenure and frequently debating on the floor. In November 1776, he shut down and then evacuated the College of New Jersey as British forces approached. The British occupied the area and did much damage to the college, nearly destroying it. Following the war, Witherspoon devoted his life to rebuilding the College.

Witherspoon was elected to Congress to replace pro-loyalist members after New Jersey learned that the delegate was against independence. John Witherspoon was the only active church minister out of 56 men to sign the Declaration of Independence. You can lift a glass in his memory at the Witherspoon Grill (57 Witherspoon Street), and inspect his grave in the President’s Lot on the southwest edge of Princeton Cemetery (29 Greenview Avenue).

The 56 Signers of the Declaration of Independence

Declaration Factoids

- The Declaration of Independence has five distinct parts: the introduction, the preamble, the body, which can be divided into two sections, and a conclusion.

- On June 21, before sending a delegation to Philadelphia, the NJ Provincial Congress at Burlington voted 53-3 to break ties with Great Britain.

- Thomas Jefferson presented a draft of the Declaration of Independence in the days leading up to July 4, 1776. The full Congress debated, revised, and edited the document on July 2 and July 3. By July 4, they ratified the wording. However, the formal copy of the Declaration of Independence wasn’t officially finalized until two weeks later and wasn’t signed until August 2.

- The New Jersey delegation had little connection with either the preliminaries or the actual drafting of the historic document. Hopkinson was the only delegation member present for the entire proceedings.

- Delaware signers were first. New Jersey was the 11th colony to sign.

- New Jersey was the third state to ratify the US Constitution on December 18, 1787. The state’s 38 electors were all Federalist supporters of the framework, selected just before the state convention. New Jersey seemingly viewed the Constitution’s ratification as a necessity because, under the new plan, the state would primarily preserve its stature in the general government and would benefit from the protection of the militia in cases of upheaval.

- Benjamin Franklin, 70, was the oldest signer of the document.

- Although Congress had adopted the Declaration submitted by the Committee of Five, the committee’s task was not yet completed. Congress had also directed that the committee supervise the printing of the adopted document. The first printed copies of the Declaration of Independence were produced from the shop of John Dunlap, the official printer to Congress. After the Declaration had been adopted, the committee took the manuscript document, possibly Jefferson’s “fair copy” of his rough draft, to Dunlap. On the morning of July 5, copies were dispatched by members of Congress to various assemblies, conventions, and committees of safety as well as to the commanders of Continental troops. Also, on July 5, a copy of the printed version of the approved Declaration was inserted into the “rough journal” of the Continental Congress for July 4. The text was followed by the words “Signed by Order and in Behalf of the Congress, John Hancock, President. Attest. Charles Thomson, Secretary.” It is not known how many copies John Dunlap printed on his busy night of July 4. There are 26 copies of what is commonly called “the Dunlap broadside,” 21 owned by American institutions, two by British institutions, and three by private owners.

- On July 19, Congress was able to order that the Declaration be “fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and stile [sic] of ‘The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America,’ and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress.”

- After the signing ceremony on August 2, 1776, the Declaration was most likely filed in Philadelphia in the office of Charles Thomson, who served as the Secretary of the Continental Congress from 1774 to 1789.

- In 1800, by the direction of President John Adams, the Declaration and other government records were relocated from Philadelphia to the new federal capital then being constructed in the District of Columbia.

- The Declaration remained safe at a private home in Leesburg for several weeks–in fact, until the British had withdrawn their troops from Washington and their fleet from the Chesapeake Bay. In September 1814, the Declaration was returned to the national capital. Except for a trip to Philadelphia for the Centennial and a visit to Fort Knox during World War II, it has remained there ever since.

- In 1876, the Declaration traveled to Philadelphia, where it was on exhibit for the Centennial National Exposition from May to October.

- The 26 copies of the Dunlap broadside known to exist are dispersed among American and British institutions, as well as private owners. The following are the current locations of the copies.

- National Archives, Washington, DC

- Library of Congress, Washington, DC (two copies)

- Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, MD

- University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (two copies)

- Independence National Historic Park, Philadelphia, PA

- American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, PA

- Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

- Scheide Library, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ

- New York Public Library, New York

- Morgan Library, New York

- Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, MA

- Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

- Chapin Library, Williams College, Williamstown, MA

- Yale University, New Haven, CT

- American Independence Museum, Exeter, NH

- Maine Historical Society, Portland, ME

- Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

- Chicago Historical Society, Chicago, IL

- J. Erik Jonsson Central Library, Dallas Public Library, Dallas, TX

- Declaration of Independence Road Trip [Norman Lear and David Hayden]

- Private collector

- National Archives, United Kingdom (three copies)

- Had the British been more aggressive and cut off Washington in Manhattan, the war could have been lost, the Declaration of Independence would have been nothing but evidence of treason — and there’s no telling what kind of history we’d be discussing today.