Is William Alexander, aka The Earl & Lord of Stirling, Basking Ridge’s Most Famous Resident?

Our researchers think so. Let’s see if we can answer that question.

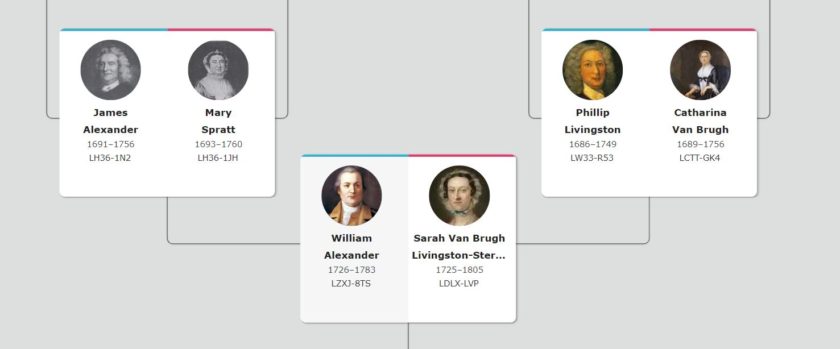

William Alexander (1726 – Jan 15, 1783) was the son of Secretary & lawyer James Alexander. His mother, Mary Spratt Provoost, was the widow of David Provoost, a wealthy New York merchant. James and Mary fled from Scotland in 1716 after participating in the Jacobite Rising in 1715. James Alexander (May 27, 1691 – April 2, 1756) was a lawyer, statesman, Secretary, and Surveyor in colonial New York. He served in the Colonial Assembly and as the colony’s attorney general from 1721 to 1723.

William Alexander was considered heir to the Scottish title of Earl of Stirling through Scottish lineage (being the senior male descendant of the paternal grandfather of the 1st Earl of Stirling, who had died in 1640), and he sought the title sometime after 1756. Raised on Broad Street in Lower Manhattan, he relocated to the countryside. He chose Baskinridge (Basking Ridge) and became what many feel is the area’s most famous resident. Let’s take a look.

Early Years

At an early age, William aspired to be an astronomer and had a passion for mathematics. But he also longed for the title of “Lord,” something his father never pursued, but a title his grandfather held as the 5th Earl of Stirling. If you have the title of “Lord,” you also have the rights and privileges back at the House of Lords in England. It was also noted that the Stirlings held title to large tracts of land in America and Canada. So, if you held the title, you retained the rights to the land your family had acquired. William Alexander, the great-grandfather, was once an official of Lord Stirling and owned tracts of land, including Maine, Nova Scotia, Block Island, Long Island, and large sections of New Jersey.

Lordship Title

The title of Lord was essential to James’s son, William, even though his father, James, never pursued it. The Earl of Stirling title would prove his aristocratic title back to Scotland and let the British know precisely who they were dealing with. William’s claim was initially granted by a Scottish court in 1759 at the age of 33. The ultimate goal was for young Alexander to re-acquire what his family had previously owned. Additionally, the sponsors would receive money and land if William were to succeed.

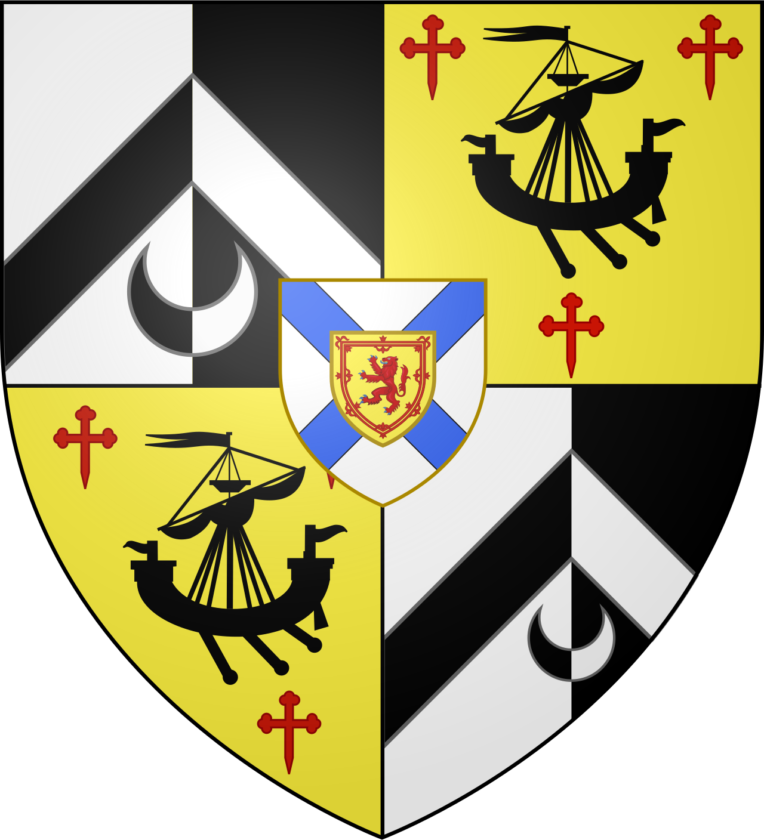

Earl of Stirling was a title in the Peerage of Scotland. It was created on 14 June 1633 for William Alexander, 1st Viscount of Stirling. He was born at Menstrie Castle, near Stirling.

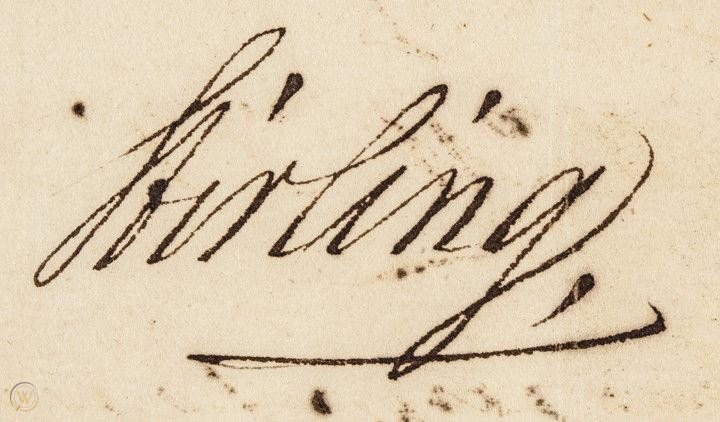

However, the House of Lords ultimately overruled Scottish law and denied Alexander the title in 1762. He continued to hold himself out as “Lord Stirling” regardless. Even General Washington sometimes referred to Alexander as “My Lord.” But the British often mocked Alexander, knowing he was NOT a “Lord of Stirling.”

Sarah Livingston as the Lord’s “Lady Stirling”

William Alexander was courting someone from a very connected aristocratic family, the Livingstons, Lords, and the like, who would later sign the Declaration of Independence and become the first post-war governor of New Jersey. On March 1, 1748, William married Sarah Van Brugh Livingston, the daughter of Colonel Philip Livingston, 2nd Lord of Livingston Manor, and her mother, Catharine Pieterse Van Brugh Livingston.

William became Lord Stirling.” Sara was known as “Lady Stirling.” It has also been said that Elenore Roosevelt is related to the Livingston name.

Sarah was also the sister of Governor William Livingston. William and Lady Stirling had two daughters and a son, Mary, Catherine (Kitty) and William. Mary Alexander would marry a wealthy merchant, Robert Watts of New York. Kitty would marry William Duer. We know very little about William Jr. and are still researching.

Pre-Rev War Moments

When the Revolution stirred in New Jersey, William Alexander, better known as Lord Stirling, was among the first to act. A man of immense wealth and pride, he did not hesitate to put his fortune behind his convictions. Appointed colonel of the New Jersey colonial militia, Stirling personally outfitted his men of the 1st New Jersey Regiment, spending freely to prepare them for war. His leadership quickly shone through when he led a band of volunteers to seize a British naval transport bristling with guns—a daring victory that earned him early respect among the Patriots.

Not long after, Stirling found himself at the center of one of the most delicate tasks in New Jersey’s revolutionary story: the arrest of Royal Governor William Franklin. The son of the famous Benjamin Franklin, William had remained fiercely loyal to the Crown. Despite his father’s growing ties to the Patriot cause, the younger Franklin remained steadfast. When Stirling intercepted one of Franklin’s secret dispatches to British intelligence in January 1776, it sealed the governor’s fate. After a brief release, Franklin’s attempt to reconvene the legislature that summer led to his final arrest and imprisonment in Connecticut, an act that marked the end of royal authority in New Jersey.

Years earlier, in 1771, Lord Stirling had purchased the vast Hibernia Furnace in Rockaway, one of the state’s largest ironworks. During the Revolution, its blazing hearths would become vital to the Continental Army, producing the iron tools and weapons that fueled the fight for independence. Stirling’s investment and management kept the furnaces alive even in the most uncertain times.

His dedication did not go unnoticed. In March 1776, the Second Continental Congress commissioned him as a Brigadier General in the Continental Army. Soon after, Lord Stirling would command the proud 1st Maryland Regiment in one of the war’s earliest and most desperate battles, the Battle of Long Island, where his courage and sacrifice would earn him a lasting place in America’s founding story.

Revolutionary War Notes

At the Battle of Long Island, Lord Stirling’s courage was put to its greatest test. Surrounded and outnumbered, he led his men in a fierce stand against overwhelming British forces. The fight was desperate, but Stirling refused to yield. His defiance bought precious time—long enough for Washington’s main army to slip away and reach the safety of Brooklyn Heights. Though captured in the end, Stirling’s sacrifice helped save the Continental Army from near destruction.

Under the shroud of a thick nighttime fog, Washington completed his miraculous withdrawal across the East River to Manhattan, preserving the fight for independence. In the aftermath, one newspaper hailed Stirling as “the bravest man in America.” Both his own commander and even his British captors admired his fearlessness and audacity. In later years, a monument would rise near the site of his valiant stand, the ground consecrated as “blood-soaked Maryland soil,” honoring the soldiers of Stirling’s Maryland Regiment who fell in his defense.

Following his capture, Stirling was exchanged for Montfort Browne, the British governor of West Florida, and returned to the army with a new rank, Major General. Washington, who deeply respected him, soon came to rely on Stirling as one of his most trusted commanders. During the winter encampment at Middlebrook in 1779, while Henry Knox was stationed at Pluckemin, Washington placed Stirling in command of the entire Continental Army for nearly two months. From his headquarters at the Van Horne House, just six miles from his Basking Ridge estate, he oversaw operations with steady leadership and loyalty.

There were also other notable moments. When General Charles Lee was court-martialed for his controversial conduct at the Battle of Monmouth, it was Lord Stirling whom Washington selected to preside over the proceedings—a testament to his judgment and integrity.

Even before these honors, Stirling’s counsel was valued at the highest level. On May 2, 1777, Washington, Nathanael Greene, and Henry Knox gathered at Stirling’s home for a council of war to debate a potential strike on New Brunswick. After careful deliberation, they agreed the troops were not yet ready. Throughout their correspondence, Washington addressed him with respect befitting his title, “My Lord”, a subtle acknowledgment of both his noble heritage and his noble service to the cause of American liberty.

Basking Ridge’s Biggest Event – Kitty Stirling’s Wedding

The summer air was thick with the scent of July leaves when the wedding of Lady Kitty Alexander and Colonel William Duer took place beneath the towering trees of her father’s estate. It was July 27, 1779, and the war still loomed close enough that guests had to pass through sentinels and military lines to reach the celebration. Governor Livingston, often reluctant but dutiful, issued passes to the guests, members of New Jersey’s most prominent families: the Southards, Kennedys, Hatfields, Lotts, and Mortons. They arrived carrying fine gifts and dressed in their best silks and lace, a striking contrast to the worn uniforms of soldiers stationed nearby.

Lady Kitty’s trousseau was the talk of the camp, hundreds of pieces of satin, paduasoy, and lace gathered from both sides of the Atlantic. Even the Duchess of Gordon and the Earl of Shelburne, friends of Lord Stirling from his London days, sent lavish tokens to honor the general’s beloved daughter. Few could have imagined that many years later, that radiant bride, once the darling of both armies, would become an aging widow in New York, forced by hardship to part with the keepsakes of her happiest day.

Family tradition tells us that Kitty stood in white beneath a great cypress tree, her gown gleaming softly in the filtered sunlight, as General George Washington himself presented her to her waiting groom. Around them, officers in their splendid uniforms mingled with ladies in bright petticoats, their laughter carrying across the lawn. After the ceremony, the company moved to the manor for a grand feast, the kind of generous colonial collation that seemed to suspend the troubles of war for just one afternoon.

As the evening light faded, the younger guests took to games, “Langteraloo,” “Kiss the Bride,” “Put,” and other long forgotten merriments. Then a commotion arose outside. Rushing to the windows, the company found the manor surrounded by soldiers from the nearby encampment, cheering and calling for a glimpse of the bride. Laughing, Lady Kitty stepped once more onto the grass in her white satin slippers, curtseying and smiling as the men of her father’s army offered their congratulations one by one before marching off again into the twilight.

That joyful wedding was Lord Stirling’s last great celebration at the manor. His devotion to the Patriot cause had drained his fortune, and by the time he died in 1784, he left behind little but honor and a noble name. Yet through her marriage to William Duer, Lady Kitty continued to move in New York’s highest circles, surrounded for a time by the same elegance and grandeur she had known at her father’s beloved Jersey home, a fleeting echo of a golden day beneath the cypress trees.

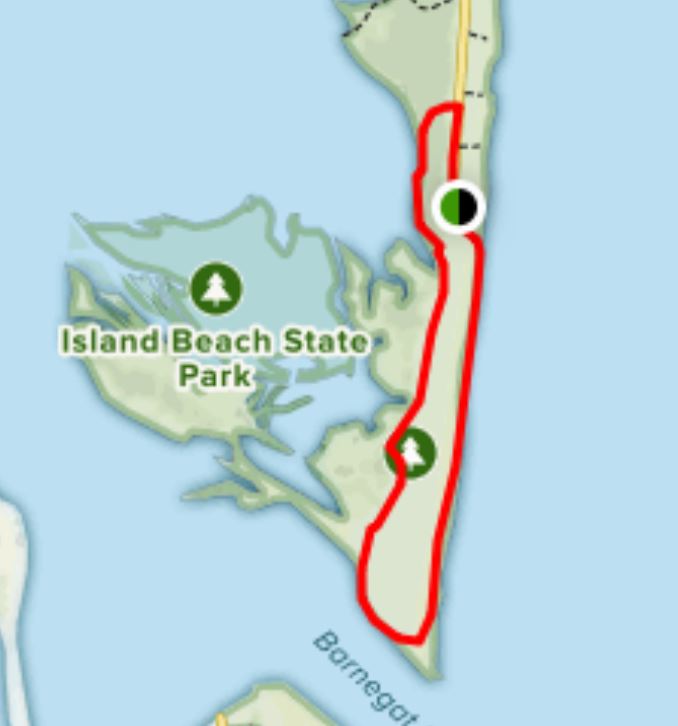

William Alexander Owned Island Beach State Park

The Island Beach State Park area was an island separated from the rest of the Barnegat Peninsula by an inlet. By the time of the American Revolution, it was owned mainly by William Alexander, Lord Stirling, who would become one of George Washington’s most trusted generals. Some maps of the time call it Lord Stirling’s Beach or 9-Mile Beach.

In July 1761, William Alexander assumed the title. Standing at the base of Barnegat Lighthouse, looking north across Barnegat Inlet, we can see Island Beach State Park. Google Maps tells us it is 50 miles away and will take over an hour to drive there. From a distance, the park looks like a time capsule of the Jersey Shore 200 years ago.

Some of the Alexander Holdings

“I have taken and levied on a certain tract of land which was William Alexander’s, Earl of Stirling, at the time of his death, situate, lying and being in the Township of Dover, called by the name of ‘Island Beach’ to the value of six pence, which remains in my hands for want of a buyer.”

In 1790, the Monmouth County sheriff posted this notice

SIX PENCE? Well, that’s 1/2 a SHILLING with 20 SHILLINGS equaling a POUND STIRLING. We’re talking $0.06 back in 1790. #THEIVES!

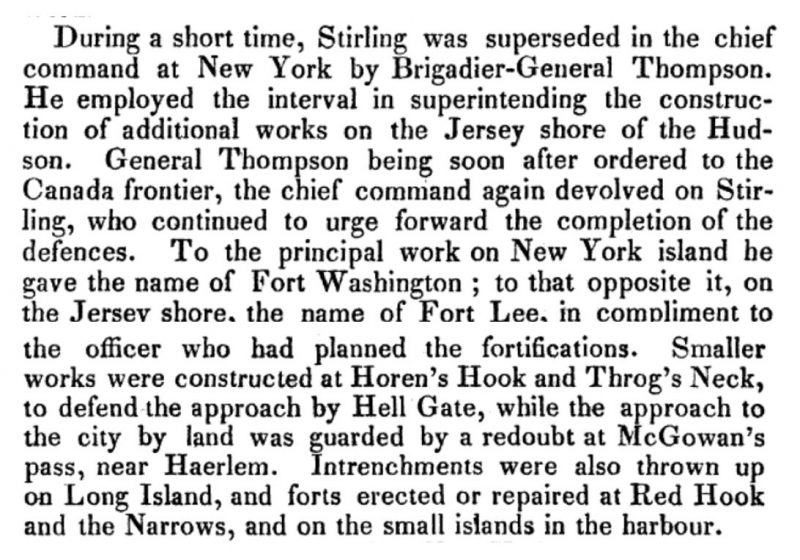

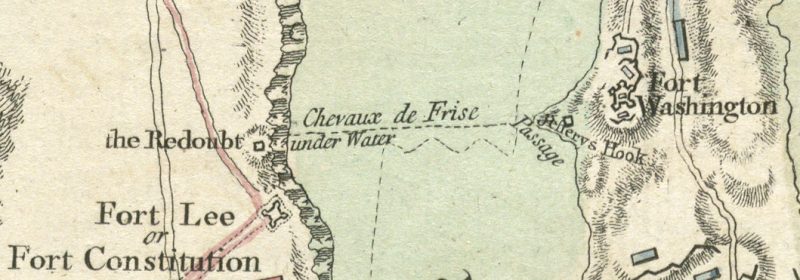

Alexander Built Fort Lee and Fort Washington

Colonel Alexander was appointed by General Washington in 1776 to fortify the heights of New Jersey and New York. He later proclaimed the reinforcement of Fort Lee in Jersey and the fortification of Fort Washington in New York.

Alexander’s Viticulture (Winemaking)

It was known that William Alexander was an accomplished mathematician who loved astronomy and horse breeding, and Stirling was also a devoted student of winemaking. Like Jefferson, Stirling dedicated much of his estate to growing grapes to produce locally produced vintage wine. It was said that the grapes originated in Italy.

The Royal Society of Arts sought to encourage the colony to cultivate grapes. With some awareness of this background of failure, the Society in 1758 offered a premium of 100 pounds to the colonists who, within seven years, should be the first to produce five tons of red or white wine of acceptable quality.

In 1767, through William Alexander’s gardener, Thomas Burgie, he advised the society that he had planted 2,100 vines. Earlier, in 1763, he had explained to his friend, the Earl of Sherburne, the difficulties that confronted an American viticulturist and had made a plea for governmental encouragement of such projects.

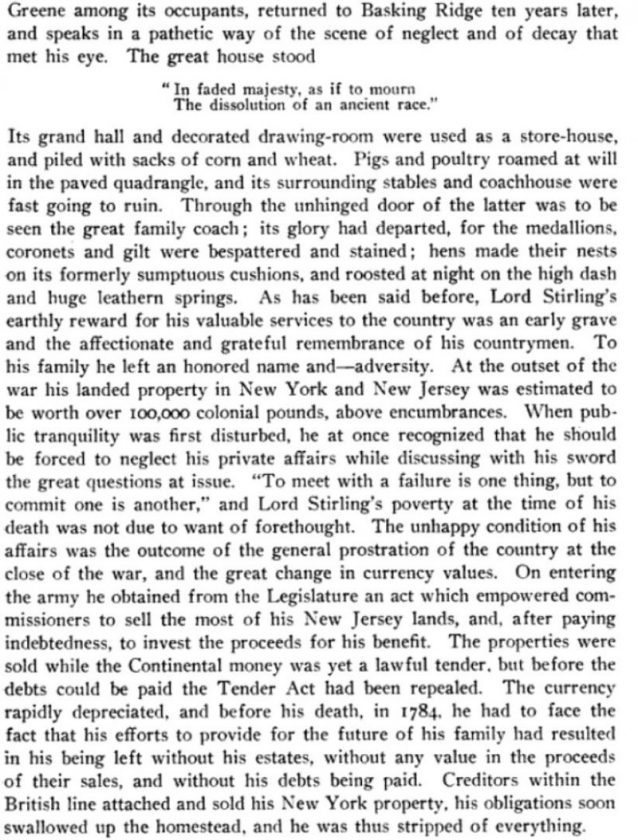

Final Days

Sadly, Stirling didn’t get to experience the official end of the war in 1783. Known to imbibe, Alexander was in poor health, suffering from severe gout and rheumatism, and died in Albany on the 15th of January 1783, just months before the Treaty of Paris was signed. He also died as a pauper, heavily in debt, leaving nothing to his children.

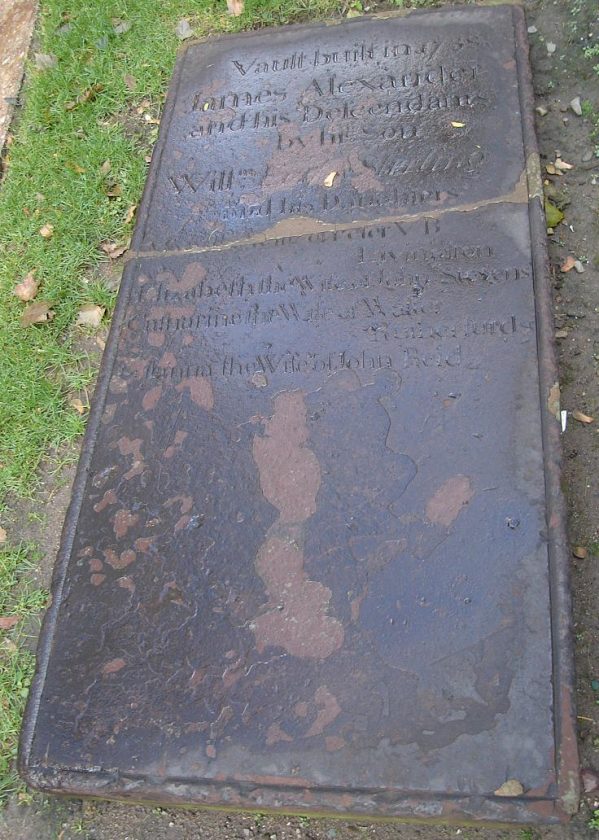

William Alexander died on January 15, 1783, at age 57. He is buried in the Trinity Church graveyard in Lower Manhattan alongside his father, James Alexander. This is the family vault of the Alexanders, including Lord Stirling (William Alexander), his father James Alexander (Surveyor General of New Jersey and New York), and several of his sisters who married into other prominent colonial families such as Livingston, Stevens, Rutherfurd, and Reid. It remains one of the most historically significant burial vaults in Trinity Churchyard.

Trinity Churchyard

Manhattan, New York County (Manhattan), New York, USA

The vault, built in 1756, includes the remains of James Alexander and his descendants, including his son William, Lord Stirling, and his daughter Mary, the wife of Peter Van Brugh Livingston; Elizabeth, the wife of John Stevens; Catherine, the wife of Walter Rutherfurd; and Joanna, the wife of John Reid.

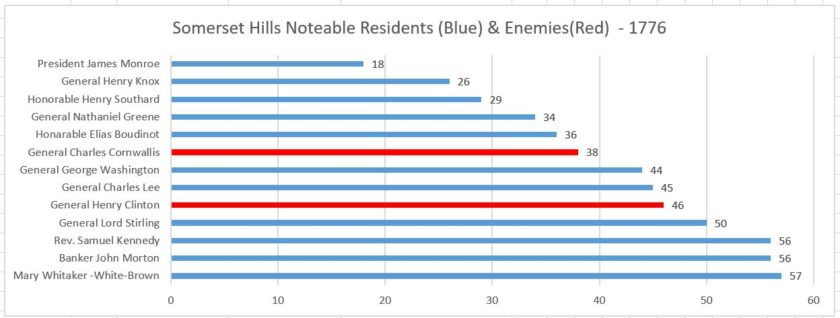

Notable Neighbors

Basking Ridge played an essential role in the Revolution. With Stirling in the area, it’s interesting to note that Elias Boudinot, the President of the Continental Congress, lived just up the street. It was also pointed out that General Charles Lee, another Major General in the Continental Army, was captured just a mile away at Widow White’s tavern on South Finley Avenue on December 13, 1777. Was he traveling from Morristown to meet Stirling? And think about how many early American dignitaries visited Stirling at the Stirling Manor. George and Martha Washington visited Basking Ridge for sure. The New Jersey Governor Livingston certainly did, considering his son married Stirling’s daughter. It’s such an excellent area for local historians. We’ll keep digging.

Source: Mr. Local History

Did You Know?

While William Alexander was building his country estate in 1761, the East Jersey Proprietors authorized another home in Perth Amboy. See the video below:

- The 1636 deed to William Alexander, Earl of Stirling (Alexander’s grandfather), included New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard, and Long Island, which was called Stirling Island for a period.

- In October 1641, William, Earl of Stirling, deeded the “Stirling Island” to Thomas Mayhew of Watertown, Massachusetts Bay. Yes, Stirling owned Nantucket AND Martha’s Vineyard.

- In 1767, the Royal Society of Arts awarded Alexander a gold medal for accepting the society’s challenge to establish viticulture and winemaking in the North American colonies by cultivating 2,100 grape (V. vinifera) vines on his New Jersey estate.

- At the Battle of Trenton on December 26, 1776, he received the surrender of the Hessian German mercenary regiment.

- When Washington and the French Comte de Rochambeau took their conjoined armies south for the climactic Battle of Yorktown in 1781, Stirling was appointed commander of the elements of the Northern Army left behind to guard New York. He was sent up the Hudson River to Albany, where he died shortly after that in January 1783.

- In 1779, General Greene removed his wife and staff from the Van der Vere house to Basking Ridge and established his headquarters at the Stirling Manor.

- Stirling’s sister Elizabeth was the aunt of John Stevens III (1749–1838), a lawyer, engineer, and inventor who constructed the first U.S. steam locomotive and first steam-powered ferry, and Mary Stevens (d. 1814), who married Chancellor Robert Livingston, negotiator of the Louisiana Purchase.

- A house is built upon the foundation of the 1825 farmhouse (this house was constructed in part on the Stirling Mansion foundations and burned down in 1920) has been converted into offices for the Park Commission.

- Stirling, New Jersey, is named after William Alexander.

- The Lord Stirling Manor site was added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 22, 1978.

- Sterling, Massachusetts, is named after William Alexander.

More Lord Stirling Mr. Local History Posts

What Others are Reading Right Now on MLH? Top Ten Weekly Posts

- A great article about Stirling Manor

- Lord Stirling and the Grapes

- The annual Lord Stirling Festival

- Take a look at the similar Proprietary House in Perth Amboy, New Jersey’s former capital and a home built by the same builder as Stirling Manor.

March 16, 2020

I live in Basking Ridge and am a Revolutionary war enthusiast. I found this article very interesting with far more details than what I knew about William Alexander. I have several questions:

1) Who wrote this article?

2) When is the Lord Stirling festival this year? I would like to visit the wine cellar

3) Does Basking Ridge sponsor a walking tour related to American Revolutionary War sites? (the only ones that I am aware of are Widow White’s Tavern (sign), Presbyterian Cemetery, Lord Stirling’s manor site, Boudinot estate, log hut hospital sign). I think that there would be some interest and generate some revenue for the town)

Thanks- Bob Wong

I did the research and wrote the article based on that research. The festival is typically the first Sunday in October and is run by Somerset County Parks Commission. No there’s not a walking tour currently, but I’ve written about most of the sites. The Basking Ridge Rev War hospital is a little dodgy on the facts but I might dig in at some point. Glad you liked the piece. I certainly learned a lot doing it. There’s a few good books on Stirling, who actually was quite a rascal with his lottery. But it is also sad he died heavily in debt and evidently had a bad drinking problem to boot.

As we continue the research – the interactive map is a virtual tour of many of the stories we’ve documented that impacted Basking Ridge – Check out – https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/viewer?mid=1Tj7UqlX8ndW1ZIFL9C93sEX7K4PHhVRt&ll=40.73559179489243%2C-74.54386265000005&z=13

Great article and I truly appreciate your efforts in gather insightful and important history about our local area. It amazes me that all of these important people who built our nation lived, worked and fought in our our backyards. Please keep it up! One thing of note, I think the compass bearing is off on the Stirling Estate map, as if you line it up with an online map of today, it would appear that E is where N should be.

Thanks for writing. You’re going to have to prove it to me. We did have to add it to the map because it wasn’t on the original we photographed.

Here is some information from Columbia University about Lord Stirling and his heavy investment in the slave trade. “William Alexander invested heavily in the slave trade. He invested in at least two voyages in 1748, and he proceeded to buy two of his own slave ships, which brought 100 slaves to New York City.” As well, the research covers the slave-trade wealth of his wife’s family (Livingston). https://columbiaandslavery.columbia.edu/content/merchant-families

Thank you so much for this information. I recently learned about an ancestor, Jacob Anderson who served under Col. Thruston out of Virginia during the Revolutionary War. According to his pension application he marched to Lord Sterlin’s building on Bareshear Ridge and was stationed there in 1777. Jacob participated in the battles/skirmishes of Piscataway and Quibbletown. I wonder if he was referring to Breses Field listed in your map.

Thanks for putting this all together! Lord Stirling was my 8x great grandfather!

@Bonnie Verberg

Lord Stirling did not have “heavy investment” in the slave trade.

He had *temporary* investment in the slave trade. He operated those 2 boats 1 time and then left the business, wanting no further involvement.

“Heavy investment” implies prolonged, sustained involvement, more than a single venture which turned him off of the whole thing.

I also find it distasteful that you show up here to attack and slander and demonize people based on common activity of the time in which they were alive.

You realize that slavery was a worldwide phenomenon then and still is today, that only a small fraction of African slaves were brought to the Americas.

You should be thanking Lord Stirling. It was due to his effort, and other slave-owning Founders, that slavery was able to be abolished.

The comment above mine is a pathetic one to see on a historically-oriented article. McPherson, leave history to people who actually care about it.

There’s nothing slanderous about noting that the owner of two slave ships was an investor in the slave trade, and arguing that the trafficking of 100 people shouldn’t count as “heavy” is simply nonsense. Nobody attacked or demonized him; if that’s how you interpret hearing about historical facts, that reflects the shame you feel and nothing else.

“It was a common activity” isn’t an excuse; the writings of most of the Founding Fathers reveal they knew it was wrong, and by 1777 they were starting to abolish it.

“Slavery was a worldwide phenomenon then and it still is today” – also not an excuse. So is pedophilia. Is that going to be your excuse for being a diddler?

“only a small fraction of African slaves were brought to the Americas” – not only is that simply not true, but even if it was; how is that possibly relevant to Stirling’s slave trading?

My own ancestors were slave owners (some even fought for the Confederacy). It’s not a sin to say that slavery is bad. If you wouldn’t defend your brother for being a pedophile, you DEFINITELY shouldn’t defend your distant ancestor who you’ve never met for human trafficking and forced labor. It’s time to grow up and stop coddling yourself.